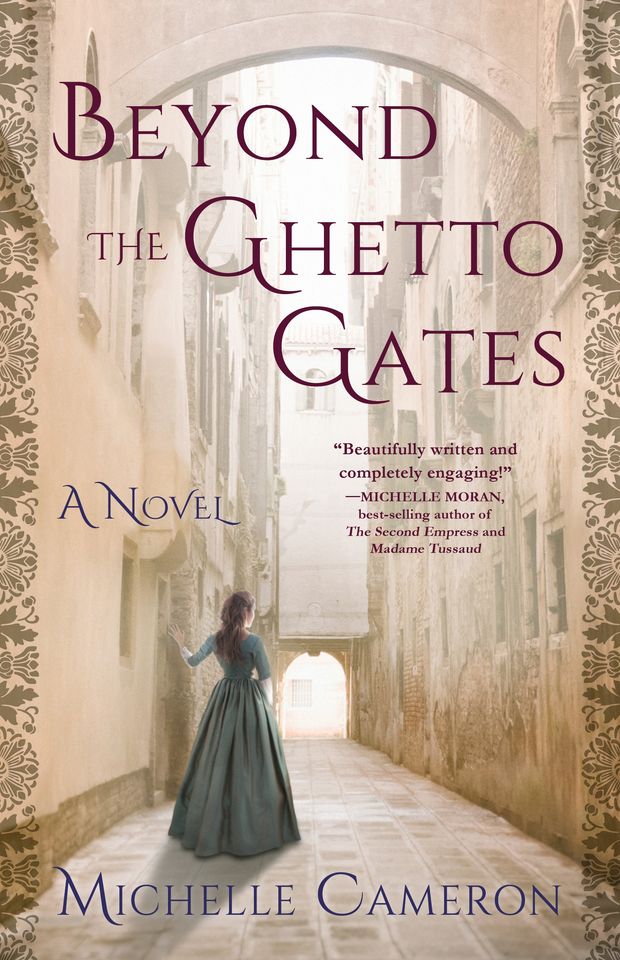

I am pleased to introduce today’s guest, Michelle Cameron. Michelle is a director of The Writers Circle, an NJ-based organization that offers creative writing programs to children, teens, and adults, and the author of works of historical fiction and poetry: Beyond the Ghetto Gates, which won the 2020 Silver Medal in Historical Fiction in the Independent Book Publisher Awards (IPPYs), The Fruit of Her Hands: The Story of Shira of Ashkenaz, and In the Shadow of the Globe.

She lived in Israel for fifteen years (including three weeks in a bomb shelter during the Yom Kippur War) and served as an officer in the Israeli army teaching air force cadets technical English. Michelle lives in New Jersey with her husband and has two grown sons of whom she is inordinately proud.

Host: Michelle, that is quite a fascinating bio. I’m excited to learn more of your work. Please tell us about about your latest project.

Guest: My Jewish historical novel, Beyond the Ghetto Gates, was published this past April. It tells the story of the 26-year old General Napoleon’s military campaign through Italy in 1796-7. When he reaches the harbor city of Ancona, he first encounters locked ghetto gates, and sends his Jewish soldiers to demolish them and emancipate the Jewish residents. Beyond the Ghetto Gates is also the story of two women – Jewish Mirelle, who must choose between her duty to her family and faith or her love for a dashing French Catholic soldier and Catholic Francesca, who is trapped in a marriage to an abusive and ultimately murderous husband.

Host: Why were you motivated to write about this time period?

Guest: My earlier historical novel took place during the rise of antisemitism and, as it included blood libels, book burning, torture, and more, in many ways it was a difficult book to write. I was explicitly looking for that rare beast – a joyous moment in Jewish history.

Host: Ah. Now you are speaking my language! Tell me more.

Guest: While reading about the Jews of the French Revolution, I happened upon Michael Goldfarb’s nonfiction book, Emancipation. In it, he describes the scene of Napoleon’s happening upon the ghetto gates. This highly dramatic moment had “novel” written all over it. One of the themes that runs through much of my writing is the tension between assimilation and safeguarding religious belief, which is why I was motivated to write about this time period. It also intrigued me because it was a historical episode many readers (and this writer) had never heard of before.

Host: I appreciate authors who weave accurate history throughout the storyline. In particular, I enjoy discovering, and highlighting, the beauty of our Jewish heritage. While doing your research, were you surprised at your findings?

Guest: While I could anticipate much of what I found in my research, there were actually two substantial surprises, both of which contributed mightily to the plotline. The first was discovering that Ancona, Italy, was the world center of ketubah (Jewish marriage certificate) making during this time. The artisans of Ancona were the first to illuminate these documents, and the ketubot (plural) had a highly distinctive shape. This shape – called an ogee arch, a rounded top culminating in a peak – allowed me to recognize when a ketubah came from Ancona in such far-flung exhibits of Judaica in Toronto, Edinburgh, and New York. It also gave my heroine a purpose and a desire: to contribute to her family’s legacy, as makers of these exquisite documents.

The second surprise was stumbling on the story of the miracle Madonna. In June, about eight months before Napoleon arrived, a portrait of the Virgin Mary in Ancona’s Cathedral purported to turn its head, smile upon the congregation, and weep. This was all documented in a Vatican recounting of the event, which included the fact that Francesca Marotti and her daughter Barbara – both characters in the novel – were the first to see the miracle.

Part of Napoleon’s campaign was the systematic looting of Italy’s artwork and religious artifacts. An anecdote tells of him denuding the cathedral in Ancona and seeing the miracle portrait. According to the story – which may be fabricated – something he saw as he stared at the painting shocked him. I couldn’t resist adding this scene! I should add that everything that happens to the portrait after Napoleon sees it is purely my invention. But the portrait itself became a critical plot device.

Host: Which of your characters resonate with you most?

Guest: I think in many ways both of the main characters have a bit of me in them – Mirelle in her feeling toward her family and conflicting desire to accomplish something that is nontraditional, Francesca in her internal sense of rightness.

Host: What is your writing process? Do you know how it will end, as you get started?

Guest: Because research is such a critical part of my novels, I begin with a three-month “deep dive” into the material, just to get my arms around it. This is when I discover what parts of the story can be derived from the research. But since I love historical research so much, I make myself limit it to that three-month period. Otherwise, I might never emerge! But I do still keep researching, of course, as I hit the many, many times when I arrive at a scene where I don’t know what I need to know – and even consult my books and other research materials when I’m in the midst of revising.

In fact, I revised Beyond the Ghetto Gates more than I’ve ever revised any other novel. I thought I did know the end when I started – but my beta readers convinced me that I didn’t! In fact, I changed both the beginning and the end of the novel multiple times. The end itself is somewhat unusual, and many of my readers have been surprised by it. (Frankly, so was I!)

Host: How long have you been writing? When did you first consider yourself an author?

Guest: I’ve been writing since the fourth grade and always wanted to become a writer. It didn’t come easily. My first three novels never saw the light of day – thank goodness! When the third was rejected, I decided that I had tried and failed, and took a hiatus from writing. It was my youngest son whose love of writing brought me back to it – which is one of several reasons that Beyond the Ghetto Gates is dedicated to him. I first considered myself an author with the publication of my first work – a verse novel about William Shakespeare and the Globe theatre, called In the Shadow of the Globe.

Host: Are you already onto the next project? When will we see it in print?

Guest: Yes, I’m already deep in research for the next novel – a sequel to Beyond the Ghetto Gates in which Napoleon does something unexpected: takes a military expedition to Egypt and Israel. So we’ll be continuing with the same cast of characters. This novel took me about three years to write, so my earnest hope is that the next book will be out in 2023 – or earlier. But we’ll see.

Host: You are certainly keeping busy! Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Guest: Here are the links to my website and social media:

Website: michelle-cameron.com Facebook Author page: /michellecameronauthor

Instagram: @michellecameronwriter

Twitter: @mcameron_writer

In addition, Beyond the Ghetto Gates can be found at all online and brick-and-mortar booksellers, including: Bookshop.org| Barnes & Noble | Amazon | Kindle | Books-A-Million

Host: Thank you, Michelle, for spending some time with us today. I believe you are leaving us with an excerpt. I know we will all enjoy the read!

Guest: Yes, the following is from Chapter Two. Thanks so much for this interview, Mirta!

Tall buildings loomed on either side of the street. Mirelle was used to the narrow space, but today the air seemed more fetid than usual, the close-packed homes more menacing. The buildings—many built centuries before and precariously expanded upward—were crumbling at their foundations. Apartments exuded the smells of a hundred cooking pots, paint curling under the sweat and filth of packed living.

Toddlers played in the streets, ignoring the refuse running down the center sewer. Housewives stopped to gossip, straw baskets crushed against their sides. The market was bustling, with vibrant oranges and lemons piled into pyramids, cut citrus samples sharp in the spring air, bundled chard and spinach, flowery clusters of cauliflower and broccoli, and long spears of artichokes piled high. Crusty breads, fruit-filled flans, and boxes of biscotti wafted enticing odors. But today all Mirelle felt were the centuries of dirt and sweat trapped inside the enclosed ghetto. The walls pressed in on her, making it difficult to breathe. On impulse, she decided to visit a different market—the one outside the gates, where she could feel sea breeze and sunlight on her face.

During daylight hours, the ornate, wrought-iron gates at the ghetto entrance were flung wide. Because her friend Dolce often designated them as a meeting spot, Mirelle knew their every nook and curve. As she’d wait, she’d run her fingers over the peeling patterns, twisting and curling. From dawn until nightfall, ghetto residents moved freely through the stone archway into the city of Ancona. As the sun dipped behind the horizon, however, city guards slammed the gates shut and chained a heavy padlock to the bars. The clang of the closing gates always raised the hair on the back of Mirelle’s neck.

It affected her generally carefree brother even more. Jacopo often railed against being imprisoned inside the ghetto. “Just once, I want to see what the sea looks like under the stars,” he’d said one night as they stood outside, straining to see more than a few inches of night sky. “Just once, I’d like to walk freely out the gate and not have someone stare at me because I’m Jewish.”

Something had stirred in her chest as he spoke. A whole world existed outside the ghetto. If only they could both walk out of the gates freely!

But they were trapped. Day or night, whenever the Jews left their homes, they were required by law to don the yellow hat and armband that branded them as different. For as long as she could remember, Mirelle had covered her brown locks with a yellow kerchief before walking in the streets. She always wrinkled her nose in the mirror as she adjusted the badge of her faith. They make us wear yellow because it is the color of urine, she’d think distastefully. And of cowardice.

Her brother might feel caught inside the enclosure of the locked ghetto gates, but she felt doubly trapped—as a Jew and as a woman.