Most everyone knows the modern quip that American Jews eat Chinese food on Christmas. Less remarked upon—but far older—is the tradition of playing chess. Its origins lie in the long and uneven Jewish experience of Christmas in Christian lands, yet its meaning has not been static. By the time of the Regency era in England, the custom no longer arose from fear, but from habit, memory, and choice.

For centuries across much of Eastern and Central Europe, Christmas Eve had been a perilous night for Jews. Authorities often warned—or compelled—Jewish residents to remain indoors during Christian holy days. Synagogues and schools were closed; travel after dark could invite harassment or violence. In some regions, Christmas celebrations coincided with pogroms and mob attacks. Rabbinic leaders, concerned for the safety of their students, prohibited leaving home to study Torah on that night. From these conditions emerged the practice known as 𝑵𝒊𝒕𝒕𝒆𝒍 𝑵𝒂𝒄𝒉𝒕.

Jews remained indoors not out of preference, but prudence. Because Torah study is traditionally associated with joy and spiritual elevation, it was avoided on 𝑵𝒊𝒕𝒕𝒆𝒍 𝑵𝒂𝒄𝒉𝒕 as a gesture of mourning—both for the immediate danger of the season and, over time, for the accumulated memory of lives lost during Christmas-time persecutions. In the absence of study and public activity, permitted forms of diversion filled the long winter hours. Chess, a game of logic, foresight, and disciplined thought, proved ideally suited. It required no public exposure, violated no religious prohibitions, and exercised the intellect. Cards and even modest gambling sometimes accompanied it, since Christmas was neither a Jewish festival nor the Sabbath.

Yet England offered a different setting. By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Jews living in London—especially in areas such as Whitechapel, or in Manchester or Liverpool—did not face the same threats that had shaped 𝑵𝒊𝒕𝒕𝒆𝒍 𝑵𝒂𝒄𝒉𝒕 on the Continent. While full civic equality had not yet been achieved, English Jews enjoyed a level of legal protection, economic participation, and physical security rare in European Jewish history. Christmas Eve was not a night of shuttered fear, but one of quiet withdrawal from a holiday not their own. Staying in was less an act of survival than of cultural distinction.

In this context, chess persisted not as a response to danger, but as an inherited custom refined by circumstance. It became a familiar way to mark the evening: thoughtful, domestic, and communal. The game itself had long resonated within Jewish intellectual culture. Its emphasis on layered strategy and consequence mirrored modes of Talmudic reasoning. Medieval authorities recognized this affinity early on. Rashi, writing in eleventh-century France, discussed chess’s educational value and even encouraged Jewish women to play. In twelfth-century Spain, Abraham ibn Ezra famously praised the game in Hebrew verse:

𝑻𝒘𝒐 𝒄𝒂𝒎𝒑𝒔 𝒇𝒂𝒄𝒆 𝒆𝒂𝒄𝒉 𝒐𝒏𝒆 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒐𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒓,

𝒀𝒆𝒕 𝒏𝒐 𝒔𝒘𝒐𝒓𝒅𝒔 𝒂𝒓𝒆 𝒅𝒓𝒂𝒘𝒏 𝒊𝒏 𝒘𝒂𝒓𝒇𝒂𝒓𝒆,

𝑭𝒐𝒓 𝒂 𝒘𝒂𝒓 𝒐𝒇 𝒕𝒉𝒐𝒖𝒈𝒉𝒕𝒔 𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒊𝒓 𝒘𝒂𝒓 𝒊𝒔.

The Ashkenazi tradition of playing chess on Christmas Eve—now more than four centuries old—originated not in leisure, but in survival. What began as a response to fear and enforced isolation endured long after pogroms waned, preserved in Hasidic communities as a meaningful custom. A Hasidic story captures the deeper symbolism of the game:

𝑶𝒏𝒄𝒆, 𝑹𝒂𝒃𝒃𝒊 𝒀𝒐𝒔𝒆𝒇 𝒀𝒊𝒕𝒛𝒄𝒉𝒂𝒌 𝒘𝒂𝒔 𝒑𝒍𝒂𝒚𝒊𝒏𝒈 𝒄𝒉𝒆𝒔𝒔 𝒐𝒏 𝑵𝒊𝒕𝒕𝒆𝒍 𝑵𝒂𝒄𝒉𝒕 𝒘𝒊𝒕𝒉 𝑹𝒆𝒃 𝑬𝒍𝒄𝒉𝒐𝒏𝒐𝒏 𝑫𝒐𝒗 𝒐𝒇 𝑹𝒂𝒅𝒋𝒐𝒗. 𝑯𝒊𝒔 𝒇𝒂𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒓, 𝑹𝒂𝒃𝒃𝒊 𝑺𝒉𝒂𝒍𝒐𝒎 𝑩𝒆𝒓, 𝒆𝒏𝒕𝒆𝒓𝒆𝒅 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒓𝒐𝒐𝒎 𝒂𝒏𝒅 𝒒𝒖𝒊𝒆𝒕𝒍𝒚 𝒐𝒃𝒔𝒆𝒓𝒗𝒆𝒅, 𝒔𝒂𝒚𝒊𝒏𝒈 𝒐𝒏𝒍𝒚, “𝑰 𝒘𝒊𝒍𝒍 𝒏𝒐𝒕 𝒈𝒊𝒗𝒆 𝒂𝒏𝒚 𝒂𝒅𝒗𝒊𝒄𝒆.” 𝑾𝒉𝒆𝒏 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒈𝒂𝒎𝒆 𝒆𝒏𝒅𝒆𝒅, 𝒉𝒆 𝒔𝒑𝒐𝒌𝒆. “𝑨 𝑱𝒆𝒘 𝒔𝒉𝒐𝒖𝒍𝒅 𝒌𝒏𝒐𝒘 𝒕𝒉𝒂𝒕 𝒊𝒏 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒉𝒆𝒂𝒗𝒆𝒏𝒍𝒚 𝒔𝒑𝒉𝒆𝒓𝒆𝒔 𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒓𝒆 𝒂𝒓𝒆 𝒇𝒊𝒆𝒓𝒚 𝒂𝒏𝒈𝒆𝒍𝒔 𝒍𝒊𝒌𝒆 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒎𝒂𝒋𝒐𝒓 𝒑𝒊𝒆𝒄𝒆𝒔 𝒐𝒏 𝒂 𝒄𝒉𝒆𝒔𝒔𝒃𝒐𝒂𝒓𝒅. 𝑻𝒉𝒆𝒚 𝒄𝒂𝒏 𝒎𝒂𝒌𝒆 𝒈𝒓𝒆𝒂𝒕 𝒎𝒐𝒗𝒆𝒔, 𝒃𝒖𝒕 𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒚 𝒄𝒂𝒏𝒏𝒐𝒕 𝒓𝒊𝒔𝒆 𝒉𝒊𝒈𝒉𝒆𝒓 𝒕𝒉𝒂𝒏 𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒊𝒓 𝒔𝒕𝒂𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏. 𝑻𝒉𝒆𝒏 𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒓𝒆 𝒂𝒓𝒆 𝒔𝒊𝒎𝒑𝒍𝒆 𝑱𝒆𝒘𝒊𝒔𝒉 𝒔𝒐𝒖𝒍𝒔, 𝒍𝒊𝒌𝒆 𝒑𝒂𝒘𝒏𝒔, 𝒂𝒅𝒗𝒂𝒏𝒄𝒊𝒏𝒈 𝒐𝒏𝒆 𝒔𝒕𝒆𝒑 𝒂𝒕 𝒂 𝒕𝒊𝒎𝒆. 𝒀𝒆𝒕 𝒘𝒉𝒆𝒏 𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒚 𝒓𝒆𝒂𝒄𝒉 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒐𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒓 𝒆𝒏𝒅 𝒐𝒇 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒃𝒐𝒂𝒓𝒅, 𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒚 𝒄𝒂𝒏 𝒃𝒆𝒄𝒐𝒎𝒆 𝒂𝒏𝒚 𝒑𝒊𝒆𝒄𝒆—𝒆𝒗𝒆𝒏 𝒂 𝒒𝒖𝒆𝒆𝒏. 𝑻𝒉𝒓𝒐𝒖𝒈𝒉 𝒔𝒆𝒍𝒇-𝒓𝒆𝒇𝒊𝒏𝒆𝒎𝒆𝒏𝒕 𝒂𝒏𝒅 𝒔𝒑𝒊𝒓𝒊𝒕𝒖𝒂𝒍 𝒘𝒐𝒓𝒌, 𝒂 𝑱𝒆𝒘 𝒄𝒂𝒏 𝒂𝒔𝒄𝒆𝒏𝒅 𝒕𝒐 𝒈𝒓𝒆𝒂𝒕 𝒉𝒆𝒊𝒈𝒉𝒕𝒔. 𝑩𝒖𝒕 𝒂𝒃𝒐𝒗𝒆 𝒂𝒍𝒍 𝒔𝒕𝒂𝒏𝒅𝒔 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝑲𝒊𝒏𝒈—𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝑲𝒊𝒏𝒈 𝒐𝒇 𝑲𝒊𝒏𝒈𝒔—𝑾𝒉𝒐 𝒓𝒆𝒊𝒈𝒏𝒔 𝒔𝒖𝒑𝒓𝒆𝒎𝒆 𝒐𝒗𝒆𝒓 𝒂𝒍𝒍 𝒄𝒓𝒆𝒂𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏.”

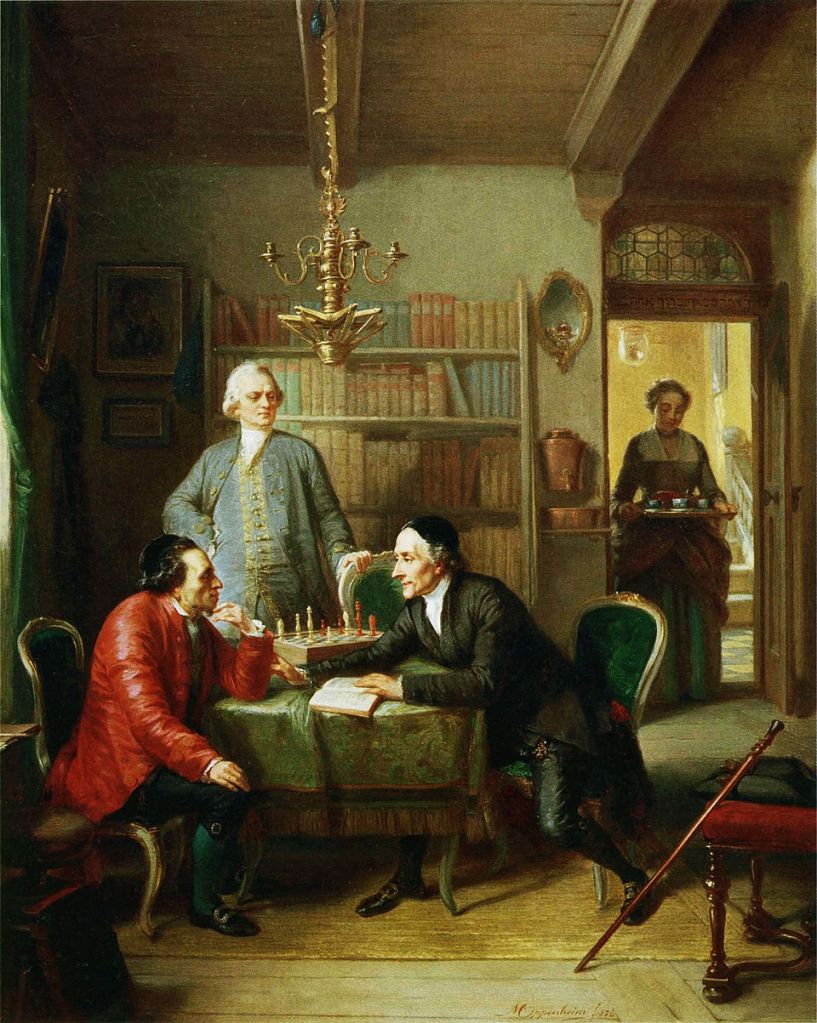

By the Regency period and certainly into the Victorian-era, chess had also become a site of Jewish cultural confidence. Jewish players were increasingly visible among Europe’s leading exponents of the game. Aaron (Albert) Alexandre, for example, emerged as a celebrated chess master and prolific writer. In 1838, he defeated Howard Staunton in a London match, cementing his reputation within England’s thriving chess world. He was followed by Wilhelm Steinitz who won the first official world championship in 1886 and Emanuel Lasker who domintated the title throughout the 19th century. Art, too, reflected this moment. In a well-known painting by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, a chess game unfolds beneath the inscription:

ברוך אתה בבואך וברוך אתה בצאתך

If you look closely, you will see the Hebrew phrase which, translated, states: Blessed shalt thou be when thou comest in, and blessed shalt thou be when thou goest out.”

The scene belongs to the age of Enlightenment, when Jewish participation in modern society was increasingly visible. Oppenheim’s chess-playing figures evoke not conflict, but dialogue—recalling, perhaps, the famous encounter in which the Swiss clergyman Johann Kaspar Lavater attempted, unsuccessfully, to convert Moses Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn’s calm refusal, calling for reason and tolerance, seems to mirror the chessboard itself, doesn’t it? A true debate is a contest of ideas conducted without coercion. At least, one can hope!

Today, playing chess on Christmas functions less as a response to danger and more as a conscious act of continuity. It is no longer an act of watchfulness born of necessity, but a way of passing the hours in quiet thought, while bearing witness to a modern world in which Jewish and Christian lives meet not in fear or exclusion, but in shared seasons and mutual respect.

Wishing you the joys of the season, with love,