Today’s post is a little bit of this and a little bit of that. It’s not an Author’s Interview—not in so many words. It’s not about one of my books—not in so many words.

You see, I didn’t interview Juana Libedinsky; in fact, it was the other way around. And while I will share a little of our conversation, this post is about the world-wide cultural phenomenon that is Jane Austen’s fandom. But let me go back and start over…

Juana is a columnist for one of Argentina’s most popular daily newspapers, La Nación, and is a cultural correspondent in New York for Uruguay’s newspaper, El País. A graduate of the University of San Andrés, she completed master’s degrees in Sociology of Culture at the National University of San Martín and in Reporting and Cultural Criticism at New York University. In addition, Juana was a New York Observer Fellow at New York University and a Wolfson Press Fellow at the University of Cambridge. Juana’s work has been published periodically in Vanity Fair and Spain’s Condé Nast Traveler. If that weren’t enough, Juana is the author of English Breakfast and Cuesta abajo—a first-person testimony about the dramatic skiing accident suffered by the author’s husband.

Before all the above was accomplished, Juana, of course, was a child much like any other. Born and raised in Argentina, her parents enjoyed attending flea markets and collected interesting objects to fill their home. I learned from Juana that, come hail or high water, the family would search through “the ugly, the kitsch, and the banal” like impassioned archeologists searching for buried treasure—much to Juana’s displeasure.

What did Juana prefer to do? She preferred reading. She discovered Jane Austen early on thanks to a distant relative, a relative with British ancestry. Partaking tea and scones whilst enjoying Austen apparently was a thing in the town of Acassuso, a locality of San Isidro. There, Juana fell in love with Austen’s happily-ever-after stories.

Unfortunately, these early reading experiences were based on poor translations that distorted the author’s original intent. Austen’s humor—that infamous irony—was all but removed by sentimental, decorous, dialogue. It wasn’t until much later, that Juana discovered the power of Austen’s genius— thanks to updated translations that were finally made available. Here Juana discovered the truth: underneath the romance, the author was a keen observer of society. Austen’s novels were actually witty commentary on class issues, gender issues, and a hypocritical society. Austen wasn’t simply an author of classics, but “a modern, ironic, political writer who was deeply observant of her social environment.”

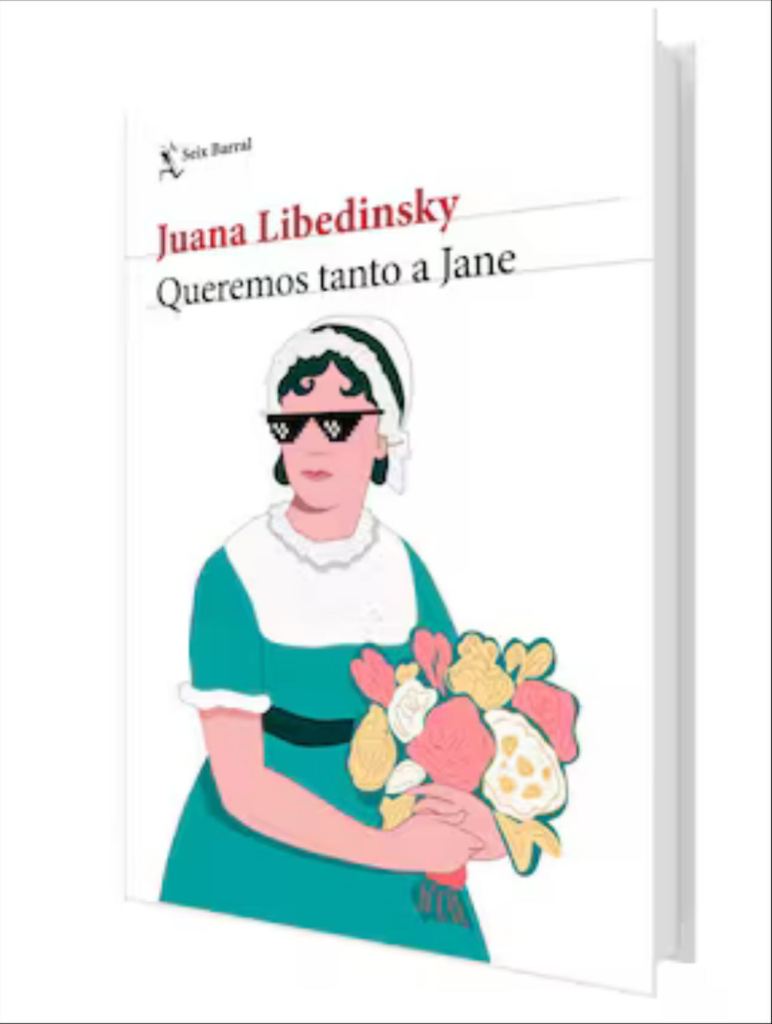

Wanting to join in the celebration of Jane Austen’s 250th birthday, Juana—along with being a wife and mother and journalist—came up with an idea for a new book. This “little book,” as she calls it, was not meant to convince anyone to love Jane or celebrate her work. Juana simply wanted to share a chronicle of adventures she undertook while experiencing Austen’s world-wide fandom.

Living in New York, Juana was fortunate enough to participate in the Jane Austen Society of North America’s various celebrations. But, it didn’t stop there! She traveled across the pond and visited London, Winchester, Bath and Chawton, attending balls, routs, and soirées in Regency attire.

“Nos llaman los Janeites. El término, utilizado ya desde el siglo XIX, designa a quienes sentimos una conexión emocional intensa con las novelas, los personajes y el universo moral de Austen. Carga con un matiz de burla –por los excesos que puede implicar esa devoción–, pero también con un fuerte componente de orgullo por la pertenencia.”

This is when Juana contacted me…when she was in England…out of the blue…to my Total. And. Complete. Shock.

Imagine it! I receive an email from this renown journalist—from La Nacion—asking if I would be interested in being interviewed for her new book.

She told me that she had read, The Meyersons of Meryton, and was excited to find that we had so many things in common.

We spoke of our love of Austen, of our ties to Argentina, and how we both experienced frustration as young readers with regards to fiction and Judaism. I laughed when I heard the trials she had experienced with her name. The “J” and “H” are quintessential problems for Spanish/English speakers. “Juana” was pronounced Kuana or Guana or Huana—it reminded me of my own experiences as Mirna, Mirda or worse yet, Merda. Ugh!

In any event, we shared emails, WhatsApp messages, and Messenger texts as Juana continued to travel. We finally set a date for the interview where I had the honor of participating in a dialogue that ended up in Juana’s book.

But she wasn’t done yet.

After traveling through England, Jane Austen Argentina was the next stop! She happily returned to Buenos Aires to partake in Austenesque activities and, of course, took the opportunity to visit her parents. They even had time to return to the flea markets in San Telmo, where she found old copies of those “imperfect” Austen translations. Juana shared that she no longer resented those works—or the time spent seeking buried treasure—because these experiences lead her to Jane in the first place. I love how she states the sentiment: “I suppose that, like Elizabeth, Emma, Anne, Catherine, Fanny, Marianne, I grew up.”

“Con picardía y erudición en el tema, Juana Libedinsky ha escrito un libro festivo, que celebra la creatividad y fineza de una autora que ha resistido la destemplada prueba del tiempo y es una voz imprescindible del canon de la literatura occidental.”

Juana’s book, Queremos tanto a Jane, was recently published. It is available in Spanish, which speaks to Austen’s popularity throughout Latin America. In the passage below, I share a translated version of our interaction (thanks to AI).

Translated excerpt from “Queremos tanto a Jane,” by Juana Libedinsky

In fact, back in Winchester, during an impromptu chat with other enthusiasts at the café across from the cathedral, I discovered an author I hadn’t heard of before: Mirta Ines Trupp. I immediately felt that her books needed to reach my Argentine friends. Her story would turn out to be as astonishing as Amy’s and her Mr. Darcy, the bookseller on Corrientes Street.

Trupp’s book, The Meyersons of Meryton, was first recommended to me. Written in 2020, it featured Jewish characters: As far as we know, Jane Austen never met any Jews, although Jewry Street—which commemorates the Jewish moneylenders and merchants who lived there before their expulsion from England in 1290—runs through Winchester, where Austen went to receive medical treatment for a then-unknown illness, possibly autoimmune, and where she died at age 41.

But that detail, Mirta told me, was secondary. I had been put in touch with her by the prestigious Jewish Book Council in the United States, an organization with which she collaborates. Mirta told me that, when she was a girl, all the stories with Jewish characters were like The Diary of Anne Frank, Fiddler on the Roof, or The Merchant of Venice. Spoiler: they didn’t end well, and she would have given anything to read one where a Jewish girl could see herself represented—without death or sacrifice.

Moreover, there are no traces of antisemitism in Jane Austen’s novels, something rare for her time. According to theologian Shalom Goldman, although the phrase “rich as a Jew” appears in Northanger Abbey, it’s not spoken by Austen herself—it comes from John Thorpe, a thoroughly unpleasant character, suggesting that Austen used the phrase to expose his pomposity and prejudice, not to normalize it.

“Jane Austen was the daughter of a clergyman; I don’t doubt her capacity to love and to recognize and value the humanity in everyone. I have faith that her most beloved characters would have been able to move beyond prejudice. In a sense, that’s what one of her greatest novels portrays,” Mirta explained to me over the phone from Las Vegas, where she lives.

Trupp’s first J.A.F.F. book introduces the Meyersons into the world of Pride and Prejudice. But it’s in her second, Celestial Persuasion, that the real surprise appears: she moves Austen’s characters to the Río de la Plata. Captain Wentworth from Persuasion crosses paths with San Martín, Alvear, and Mariquita Sánchez de Thompson, as well as with young English Jews who arrive, full of hope, drawn by the ideals of independence in a land free from inquisitions and persecution.

Of course, all of that serves as a backdrop for a grand love story.

Mirta was born in Buenos Aires, but when she was very young her family moved to Houston and, later, to Los Angeles. “My dad started working with Pan Am. That allowed us to travel to Argentina frequently—sometimes, for several months at a time; my life was always with one foot on each side,” she says.

In high school, she read Pride and Prejudice as part of the curriculum—and lost her mind. “The classic story: I fell in love with English history, with the fashion of the era, and above all, with Mr. Darcy. I could never think of anyone else again,” she laughs.

Although—she did. She met her “Mr. Darcy from Almagro,” as she naturally calls him, during one of her trips to visit family. They married in California, had three children, and later moved to Las Vegas. But it wasn’t until the kids left for college—and the empty nest syndrome hit—that Mirta began writing her Austen adaptations.

“I had already done something autobiographical about my ancestors who came from Russia to the Jewish colonies in Entre Ríos and La Pampa; then I wrote a couple of fiction books about that. It was something I enjoyed researching, and I did it for fun, but I got so many comments, so many requests to continue, that I began to investigate what might have happened to Jews who arrived even earlier—and that became the theme of a new novel.”

The spark was the 1813 painting entitled, The National Anthem in the Home of Mariquita Sánchez de Thompson—the scene of the anthem’s first performance—an oil by Pedro Subercaseaux that hangs in the National Historical Museum. When Mirta saw it, she had an epiphany. The women, in their empire-waist dresses, could have stepped straight out of a Jane Austen novel. And though the painting doesn’t identify everyone depicted, it’s believed that one of the military men represents Martín Jacobo Thompson, Mariquita’s husband and Argentina’s first naval prefect, who trained in the British navy and maintained ties with English sailors all his life.

For Mirta, the conclusion was immediate: “He could easily have been friends with Captain Wentworth! And through him, could have met Mariquita, San Martín, Alvear… All of them were highly educated and could have crossed paths with English Jews of certain standing and education in England who, through the navy, also came to know the southern part of the Americas.”

In Persuasion, Captain Frederick Wentworth proposes to Anne Elliot when they are young, but she rejects him under family pressure—he had no fortune or position. Hurt, he goes to sea. Austen’s novel mentions some ships and destinations, but she never specifies a route or offers detailed geography. What matters is that Wentworth returns triumphant and wealthy enough to marry her, completely reversing his initial situation.

For Mirta, this means he could have been in the Río de la Plata—and that when he returned to England, his heart wasn’t entirely closed to a second chance with Anne thanks to the “persuasion” of the good friends he had made there.

The book is utterly charming, and today—to her surprise—Mirta has become a recognized figure in the world of Jane Austen retellings. Scholars consult her for research; she participates in conferences, book fairs, and podcasts commemorating the 250th anniversary of Austen’s birth.

She admits that jumping between Las Vegas, Regency England, and the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata isn’t easy—but she has the time now. “I retired last year from my job within the local government. My husband and I don’t go to casinos, and we’ve already seen Céline Dion and The Phantom of the Opera too many times, so now I can dedicate myself to this.”

What she loves most, she says, is when she’s invited to Jewish book fairs. “I go dressed as a Regency character, bring extra costumes, and people—the ones you least expect—get interested and sometimes even dress up too. Around me, there are brilliant books about the Inquisition, the pogroms, the Holocaust, the current surge in antisemitism. Clearly, I’m not Tolstoy. But there’s always a line at my booth. And if what I do serves, even just a little, to lift people’s spirits, I think Jane Austen would have approved.”

I am thrilled to have participated in Juana’s inspired project. To say that it was an honor to have been included along with other renown authors, professors, and academics doesn’t suffice. There is something very special about sharing this interest—this love—with other Janeites. I’m certain that Juana’s experience with Austen’s fandom was just the beginning of many more brilliant opportunities to gather, to discuss, and to debate the genius of Austen.

Juana—Juanita—I hope you’ll call me before you go on your next world-wide tour, because—to paraphrase your own words—I don’t want to take off my empire dress anymore!

Here’s to more celebrations and more engaging conversations!

With love,