In The Jews of Donwell Abbey: An Emma Vagary, I weave a unique backstory into Jane Austen’s novel and allow Miss Harriet Smith to come to the forefront. Austen gives us a glimpse at this secondary character, this “natural daughter of nobody knows whom.” Readers must form their own conclusions—until the very end, when Austen provides a sentence or two in an attempt to wrap things up. But does she attempt to satisfy our curiosity—or does she mean to tease? In the famous Grimm’s fairy tale, Hansel and Gretel drop crumbs along their trail, leaving a path for others to follow. Can you guess where I’m going with this? Naturally, I had to follow the crumbs Austen left behind. There was another story to tell—I was sure of it—one with new characters and a Jewish storyline.

Austen provides a scenario in “Emma” that set my creative wheels in motion. I don’t want to reveal too much; but, for those of you who have read the original novel, the chapter that sends Mr. Elton off to London with Miss Smith’s portrait in hand provided my first crumb. A plot unfolded easily enough in my mind. The challenge was to ensure that historical events matched Austen’s timeline. You see, in other novels, I’ve used my own family’s immigrant experience to authenticate my protagonist’s journey. However, the exodus from Imperial Russia did not coincide with the Jewish population in Regency England. I had to look elsewhere. The timeframe allowed for a population of a majority of Sephardic Jews and a smattering of Ashkenazim of German descent.

This second crumb sent me whirling further down the rabbit hole until the Weiss family was created and I placed them in London. They were an immigrant family; their original home, I decided, was in the Judengassin—the Jewish ghetto in Frankfurt. I had to find the impetus for their migration, something catastrophic that opened the ghetto gates and allowed for their freedom. And here is the conundrum that all authors face. A plot is conceived, the players are named, but the story cries out for historical accuracy. It may only be a few sentences; but, as any author will tell you, that sense of time and place requires hours and hours of research. And that was precisely what happened to me.

Without batting an eye, I could tell you about the Jewish Colonization Association and the immigration from Imperial Russia to Argentina. I could describe the lives of Jewish gauchos or the “cuentaniks” of Buenos Aires. What I can’t—or couldn’t—do is explain how immigrants fleeing Germany’s infamous Judengasse (Jewish Street) found their way into an Austenesque novel.

Research, my dear reader, research…

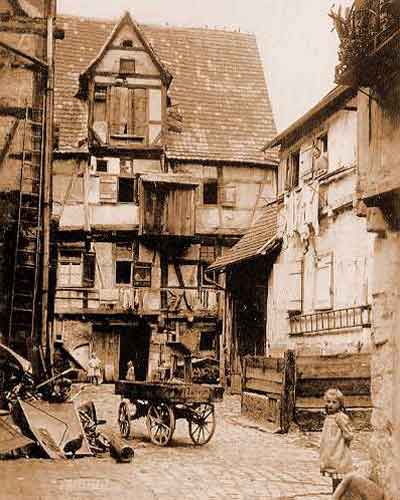

In Heinrich Heine’s book, “The Rabbi of Bacherach,” the narrative unfolds in the 15th century where Kaiser Friedrich III and Pope Pius II demand that twenty Jewish families be removed from their homes and resettled in the Judengasse. By the year 1500, approximately 100 people live in the area nicknamed, “The New Egypt.” One hundred people in 14 houses. By 1600, there were 3,000 people living in 197 houses, wooden structures that were crammed together, story upon story until they blocked out the sun, reduced air flow, and created hazards that resulted in massive fires—three of historic consequence in 1711, 1721, and 1774.

Rabbi Naphtali Cohen was called to Frankfurt am Main after his house was destroyed on January 14, 1711. Summoned to testify before the court, it was noted that the fire consumed the entire Jewish ghetto, but the rabbi—known for his Kabbalistic practice—had had the audacity to survive. Not only did he survive, the kabbalist was accused of “preventing the extinguishing of the fire by ordinary means.” The rabbi was accused of witchcraft and summarily thrown into prison. He was set free by renouncing his title and practice.

Juda Low Baruch, otherwise known as the poet, Ludwig Borne, lived in the ghetto during the late 1700s. His memories are bleak, to say the least. “The highly celebrated light of the eighteenth century has not yet been able to penetrate [the Judengasse].” His writings expressed disgust, anger, despair—futility. “If one were to consider play in childhood as the model for the reality of life, then the cradle of these children must be the grave of every encouragement, every exuberance, every friendship, every joy in life. Are you afraid that these towering houses will collapse over us? O fear nothing! They are thoroughly reinforced, the cages of clipped birds, resting on the cornerstone of eternal ill-will, well walled up by the industrious hands of greed, and mortared with the sweat of tortured slaves. Do not hesitate. They stand firm and will never fall.”

Adolf von Knigge, a German author, blamed the horrific living conditions on his Christian brethren. In his work entitled, “The Story of My Life”, he reminds his audience that these Jewish families were once “craftsmen, wine-growers and gardeners.” They once lived freely and contributed to society; however, “ecclesiastical ordinances” reduced them to peddling and to “practices of usury.” The very people who condemned this once-proud society to live in squalor, were the first to criticize and ridicule. For Knigge, these actions were the very antithesis of an enlightened society. His work was known to speak out against “aristocratic courtly culture as [being] superficial, immoderate, and wholly lacking in inner values.”

In his novel, “Labyrinth,” Jens Baggesen describes the inhuman living conditions he witnessed in the Judengassin of Frankfurt. This Danish-German author advocated for German Jews, locked behind ghetto gates night after night, not to mention Sundays and on all Christian holidays. How could an enlightened society allow such a thing? They were denied the pleasure of open air, of walks in the parks and plazas. They couldn’t patronize restaurants or coffee shops, or “walk more than two abreast in the street.” Baggesen leant his voice to the growing movement for civil rights and Jewish emancipation.

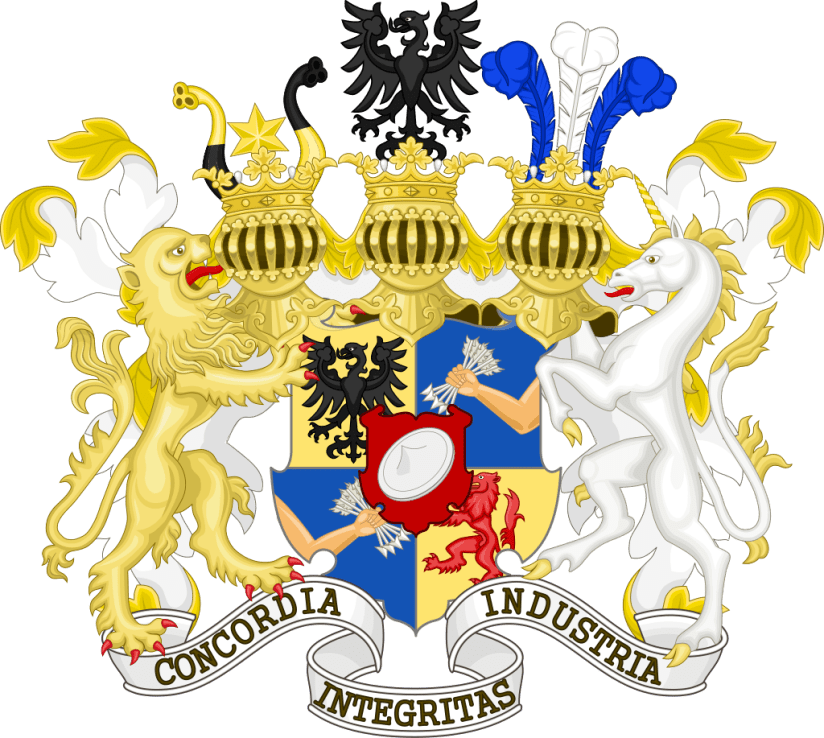

Many people have heard the name Rothschild. Mayer Amschel Rothschild and his descendants are very likely the most famous people to have lived in the Judengasse. Their surname evokes images of great wealth and power. For some, the name inspires thoughts of moxie and resourcefulness. For others, it inspires thoughts of greed and manipulation. What is the truth?

By 1560, Mayer’s ancestor, Isak, was confined to living in the ghetto. It was common for residents to be known by their address, so the family surname was most likely taken from the red shield (zum roten schild) that hung at their front door. Isak and his family were known to be pious and relatively successful cloth merchants. By the time Isak died in 1585, he had accumulated an income of 2,700 gulden. His great grandson, Kalman, had an income more than twice as large, and his son, Moses—Mayer Amschel’s grandfather—continued to prosper by not only dealing with silks and other costly materials, but with rare and foreign coins. This was not an unusual practice; Frankfurt was centrally located and was popular with businessmen from various neighboring towns and countries—not to mention noblemen and politicians.

Mayer’s father, successful merchant and patriarch, continued to live in a modest home with his family. It had been designed to suit their business needs, with an office on the ground floor, a kitchen on the first floor, and bedrooms on the top level. Mayer was allowed to attend rabbinical school at Furth, although he later was known to have said that he “only studied his religion in order to be a good Jew.” When both his parents succumbed to an unknown, but inevitable, epidemic that attacked ghetto inhabitants, Mayer’s studies came to end. He returned home for a brief time, before being sent to Hanover to apprentice with his father’s associate, Wolf Jakob Oppenheim.

Mayer was just twelve years of age when his journey into the privileged and elite world began. He learned what it meant to be a “court Jew,” garnering knowledge from Oppenheim’s family, court agents to the Austrian Emperor and the Bishop of Cologne. He learned how to work with aristocrats who were always in the business of buying and selling rare coins, jewels, and medals. In this manner, Mayer returned to Frankfurt, somewhere around 1764, a prosperous and renown businessman. In 1769, he was granted the title of court agent. In August of 1770, at the age of twenty-six, he married his beloved, Gutle, the sixteen-year-old daughter of Wolf Salomon Schnapper, court agent to the Prince of Saxe-Meiningen. All this success, and yet, he and his wife were confined to the ghetto.

Mayer and Gutle went on to have a large family; nineteen children were born, ten survived. While Gutle managed home and hearth, Mayer continued to grow more prosperous. By the mid-1780s, the Rothschilds had accumulated approximately 150,000 gulden and were able to move into a new home—substantially larger, yet still behind the ghetto gates. The new house, known as “the green shield” (zum grunen schild—they didn’t change their name at this point), was approximately fourteen feet wide. The rooms were narrow and cramped. The children all slept together in the attic. Still, it was considered to be a desirable residence. It had its own water pump! The lavatory was outside in a small courtyard. From these humble beginnings, a powerful and philanthropic family emerged.

To this day, the Rothschilds are criticized, judged, and maligned. Everyone has an opinion on their legacy. Perhaps, like Rabbi Naphtali Cohen, it would have been better if they had succumbed to their wretched circumstances. Perhaps they should have had the decency to fail miserably. Perhaps it is envy that is behind the contempt for the Jew.

The antisemitism we are living today does not differ much from what we have seen in the past. But that’s why understanding our own history, even in the form of “light” historical fiction or so-called, “Chick Lit” is vital. The past may reveal many injustices, but it also reveals our courage and our determination to survive—and to thrive.

Dignity is a powerful thing. We shall use it to break through the walls of the ghetto and set ourselves free.” – Sara Aharoni

I set out to show you how one simple thought can lead to hours and hours of research. And that, I have done.

I needed to piece together the whys and wherefores in order to bring my fictional Weiss family to London, England. And that, I have done.

I didn’t realize that this post was going to end up being some sort of call to arms. If I have encouraged you to be proud of your heritage, to advocate for justice, to look to your non-Jewish friends for support, to fulfill your dreams and destiny; then, I am glad to say: that I have done! I suppose that’s what happens when you follow one little crumb.

That being said, the original point of this post was to show how all. that. research. led to this short excerpt. I hope you enjoy!

It was September 1794. Hannah Weiss, a young woman who had not yet reached her majority and had no real knowledge of the world beyond the four corners that united her neighborhood, believed herself to be in love with Yaacov Kupperman.

Left quite unrestrained by parents who were otherwise engaged in rebuilding their lives in a foreign land, Hannah and Yaacov’s childhood friendship blossomed. They shared the love of the written word and the love of adventure. Stolen moments were spent sharing tidbits of knowledge, whether acquired from the streets teeming with intriguing activity or from passages within a tattered book. Whispered promises and fanciful dreams became woven into their very existence. It seemed so natural a thing. They spoke of their future lives with the same assurance that their mothers would bake sweet challah for the Sabbath and their fathers would sleep through the rabbi’s sermon the following day. It was inevitable. It was bashert—it was meant to be.

On a cool, temperate evening, unencumbered by chaperones or naysayers alike, the besotted pair anticipated their wedding vows. Yaacov murmured his pledge to be Hannah’s knight in shining armor, such as the men from days of yore. He vowed to protect her, to provide for her. There would be no more talk of the Judengasse, of poverty, or fear. They were English now, and their lives would be the stuff of fairytales.

“You will speak with my papa?” Hannah whispered. “You will come by us for Shabbes?”

Yaacov gently tugged on a golden curl. “Do not speak in that foreign manner, my sweet one. Instead, you should say: Will you come to our house for the Sabbath? We are native Londoners, even if our parents were born in Frankfurt. Let us not speak as if we were still in the ghetto.”

“You would admonish me now?” she bristled. “After we—after just—”

“You are such a little girl! See how you blush!” Bringing her closer, Yaacov whispered, “Never fear, my dear heart. I will speak with your papa and should be pleased to share the Sabbath meal with your family. How else will I earn my mother-in-law’s favor?”

Hannah smiled at his teasing but persisted with her train of thought. “What of your papa? Oughtn’t you speak with him first? Perhaps now, you may become his partner!”

“Perhaps,” he chuckled. “My father certainly has high hopes for the family business. I will speak with him on the morrow after he has broken his fast. Rest assured, my love. We shall be wed before Chanukah.”

Later that evening, Hannah peeked out her window and gazed into the heavens. She sent up a prayer asking for forgiveness. She was not so ill-bred that her earlier actions did not cause her some shame. Perhaps they ought to have waited until after the words had been spoken—after they had stood under the wedding canopy and the rituals had been commemorated.

I shall be married soon enough, and all will be well!

Hannah murmured another grateful prayer, for her dreams would soon be fulfilled. By December, she would recite the blessings over the chanukkiah, the precious heirloom that had been in the family for generations. It would soon be passed on to the newest bride.

September went by in a flurry. October and November, although bathed in vibrant hues of red and gold, foreshadowed the bitterness that was yet to come. Hannah could not take pleasure in the riot of colors that fell upon the city, not when her eyes were clouded with remorse. Yaacov had not come for Shabbes that Friday evening. Indeed, he had not been seen for many months past.

Hannah considered asking for him at synagogue after services or when she encountered Mrs. Kupperman at the butcher, but the unspoken words stayed upon her lips. How would she respond if they questioned her? It was not becoming for a young, unmarried girl to ask after a young man, even if they had been friends and neighbors throughout their youth. People were certain to talk. To be sure, in this matter, there was no distinction between the ghetto of Frankfurt and the streets of London.

See what people are saying about “The Jews of Donwell Abbey: An Emma Vagary” and get your copy today!

With love,

You’re so brilliant and passionate! Wow. Im reading your book. It baffles me

I’m here to baffle…I mean, I’m here to please! 🙂 Keep on reading! I look forward to hearing your thoughts. Thanks, as always!