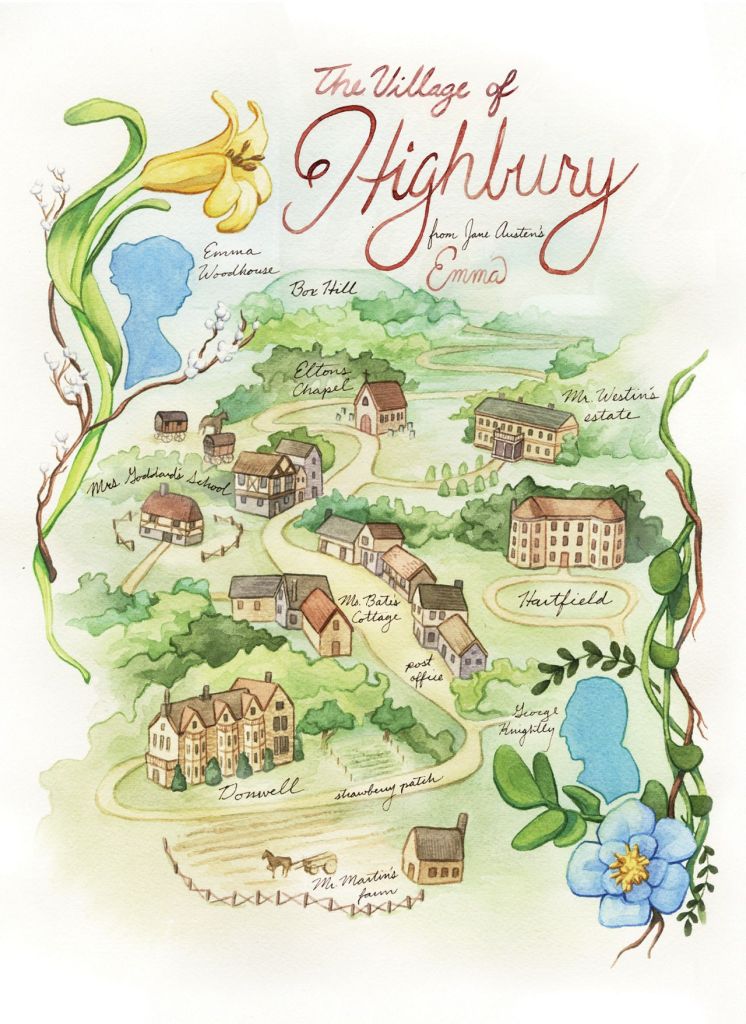

In “The Jews of Donwell Abbey: An Emma Vagary,” the spot light is on Miss Harriet Smith. As stated—so succinctly, I might add—by Mr. Knightley in the original novel, she is the “natural daughter of nobody knows whom.” Austen’s famed protagonist and resident know-it-all, Miss Emma Woodhouse, assumes she knows her prodigy’s genealogy; however, as the story unfolds, her imagination does not serve her well. Yes, I will say it: Miss Woodhouse is rather clueless. More to the point—and the reason for this post—Mr. Knightley’s admonishment provided enough encouragement to write my own version of Austen’s “Emma.”

No, that’s not quite right. I wasn’t encouraged. I was provoked!

In my previous post, I referenced Hansel and Gretel from the famed Grimm’s fairy tale. We all remember how these youngsters left a trail of bread crumbs, hoping others would follow. Whether or not Austen meant to tease future authors of fan fiction with a few suggestions, or hints, is irrelevant. I relished the opportunity to gather said crumbs and gently fold them into a new version, one that incorporated a Jewish storyline. It was a natural progression for me, but I understand that some readers might question the legitimacy of such a plot. They may ask if the Jewish population in Regency England could merit such diversity and inclusion in an Austenesque novel.

The answers were waiting for me as I tumbled down the rabbit hole…

Sometime around 1690—when exiled Jews were allowed to return to England— a synagogue for the Ashkenazi community was constructed in London. At the time, it was known as Duke’s Place Synagogue, and was probably one of the earliest of its kind.

Six or seven years later, additional land was acquired for the establishment of a Jewish cemetery. By 1722, the congregation had outgrown the original structure and a new building was consecrated, thanks mostly to the philanthropy of Moses Hart. Some six decades later, between 1788 and 1790, with the influx of Eastern European immigrants, the Great Synagogue of London was redesigned in order to accommodate its growing numbers. The principal donor, this time, was Judith Levy, daughter of Moses Hart.

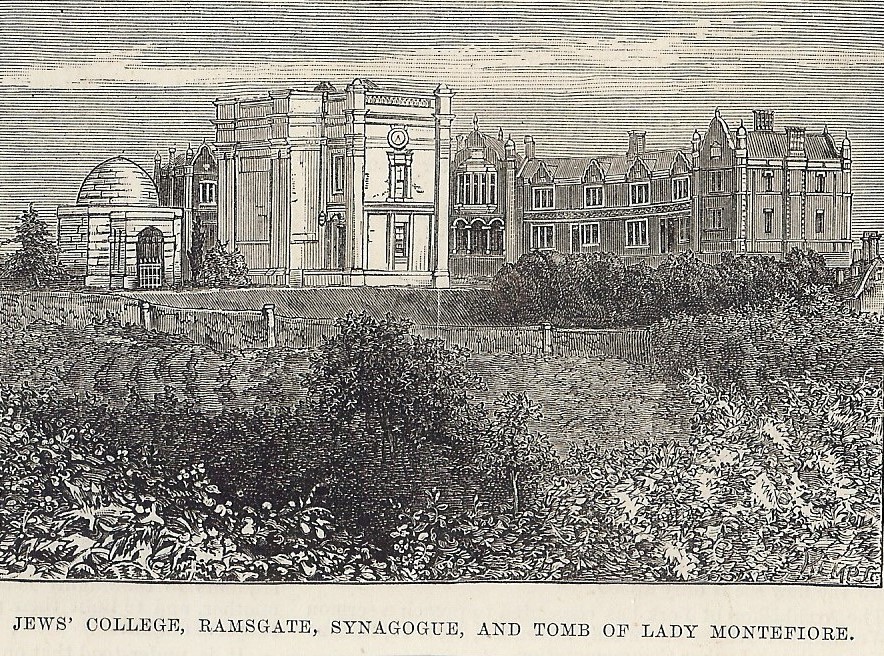

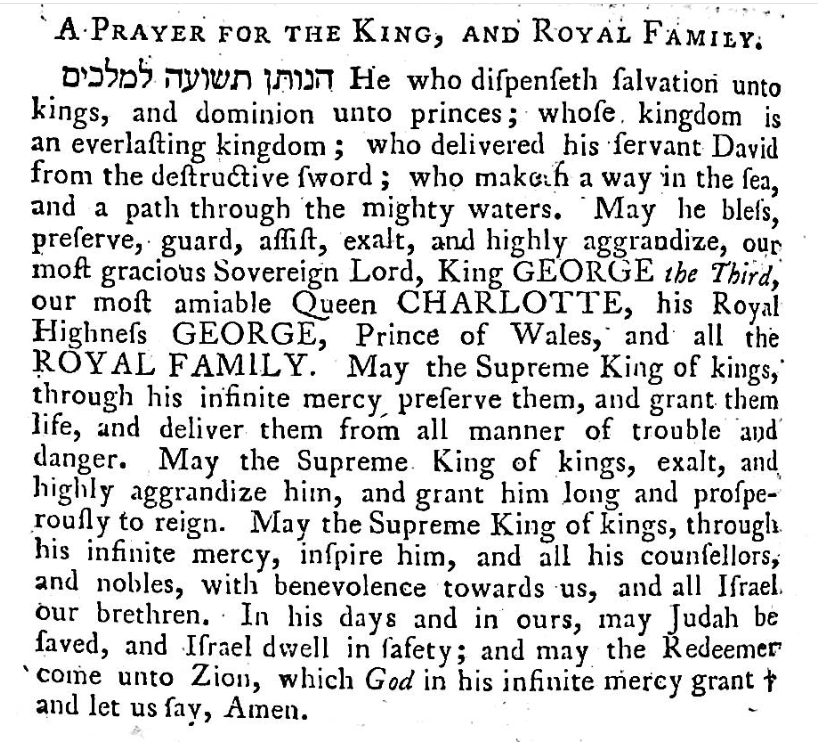

Of course, there were other Jewish communities outside of London. Synagogues, schools, and cemeteries could be found in Cornwall, Dover, Exeter, Plymouth, Ramsgate, and Sussex to name just a few. Prayer boards were typically paced in the entryways of these sacred spaces, the ancient words were made readily available for all who wished to pray on behalf of the royal family.

A Society for Visiting the Sick was established sometime around 1722, as well as A Society for the Cure of the Soul (Hebrath Refuath haNephesh). There was as an Orphan Aid Society (Hebrath Gidul Yethomim) and a society for “dowering poor brides.” Another group helped the destitute with clothing and other provisions, and a Society for Ransoming Captives (Hebrath Pidion Shevuyim) was created to “help those reduced to slavery by the barbarous customs of Mediterranean or Muscovite warfare.”

Such institutions had always formed an important part of the Jewish community, but as Anglo-Jews strove to assimilate, and be accepted in English society, it became evident that something else had to be done in order to retain—and to motivate—the community to remain religiously observant. In 1789, David Levi published a new daily prayer book (a siddur), the first publication of Hebrew liturgy with English translation.

Therefore, the answer to the posited question is: Yes! There was sufficient numbers of Jews to merit a Jewish storyline in an Austenesque novel—if, indeed, one actually needs to rationalize or justify the need for a Jewish storyline, but I digress.

In fact, the Jewish population of England was over 18,000 by the time Austen introduced her readers to Miss Emma Woodhouse and friends in 1815. By 1880, the number soared to over 60,000! While a normal person might be satisfied with that level of research, I’m here to tell you that my quest was not yet complete.

My ancestors left Imperial Russia somewhere in between 1899 and 1910. They immigrated to Argentina. During that same time period, Ellis Island was receiving wave after wave of immigrants from all across Eastern Europe. But what was going on over in Western Europe, and how could I use those events to get my fictional character, Doctor Yosef Martsinkovsky, to Surrey, England?

Austen fans are sure to know about The Napoleonic Wars, which lasted from 1803-1815. These conflicts had monumental ramifications throughout Europe at large, but the timeframe didn’t coincide with my story. I needed something of similar magnitude; and so, I followed the trail through the rabbit hole once again…

The Seven Years’ War was an attempt to prove dominance. The “usual players” involved included: Prussia, Hanover (a separate state at the time) and Britain battling against Austria, France, Spain and Imperial Russia.

The conflict raged on from 1756-1763, at the same time the British colonies in North America were making their voices heard.

Over in Prussia, Frederick the Great was busy…being not that great. His “Revised General Privilege” doctrine of 1750 allowed for the exploitation of successful Prussian Jews and the persecution of all others. In many instances, the population was worse off than their contemporizes in other lands; and, now — whether facing danger on the battlefield or facing danger at home—these Jewish communities were at the point of extinction.

The Seven Years’ War is often referred to as the first true world war. Upon its conclusion, and after all the treaties were signed, the world was a different place. Taking advantage of the First Partition of Poland in 1772, Frederick the Great expelled thousands of Jews from their homeland. This research, by the way, not only helped draft my outline, but also corroborates my family’s understanding of how our Trupp ancestors migrated from Lithuania to Ukraine. Again…I digress.

Having resolved two points that needed substantiating, I was ready to move on. Please take a moment to enjoy the excerpt below, where Mr. Knightly addresses the party at Hartfield and introduces Doctor Martsinkovsky to one and all.

Excerpt from The Jews of Donwell Abbey: An Emma Vagary :

Mr. Knightley began to pace, attracting the company’s full attention. “My father, the Colonel,” he declared, “owed his life to Doctor Martsinkovsky.”

“You have the right of it, good sir!” cried Mr. Woodhouse.

“Oh, dear! I do hope you will spare us some of the details, Mr. Knightley,” cried Miss Bates. “Pray remember we have yet to dine. Is that not right, Mama?” she said, patting her matriarch’s wrinkled hand. “Would that you could save the details for when you and the other gentlemen are enjoying your port and cigars. We are rather delicate, are we not Mama, and do not wish to hear that which might ruin our appetite.”

Mr. Knightley did not offer a reply, though he did perform a curt bow. Harriet felt a great story was about to unfold as the gentleman began his discourse, inviting one and all to recall the summer of ‘57.

He asked the party to recall how great armies had been on the move, not only on the continent but across the ocean in the Americas. Complex strategies had moved the King’s men like chess pieces upon a checkered board. Mr. Knightley reminded those old enough to remember how Austria united itself with France and how Frederick II, in turn, aligned his kingdom with the English Crown.

“And with that, Prussia’s invasion of Saxony brought the leading nations of Europe to war,” said Mr. Knightley. “Frederick not only required English funds to support his campaign, he required English troops.”

“How could anyone of us forget, sir?” asked Mr. Weston. “Only think of the men we lost—just in this parish alone—I will never forgive the king’s own son for causing so much pain. The coward!”

“Do allow Mr. Knightley to continue, dearest,” said Mrs. Weston, laying a soothing hand upon her husband.

“It is true; the Duke of Cumberland was sent to command the Hanoverian Army. His regiment, the 1st Battalion of Grenadiers, included my father. The Grenadiers were sent to support the Hanoverians—nearly 40,000 strong—to prevent French troops from crossing the Weser River. My father proposed that men be strategically placed to defend the Rhine; however, the duke rejected the plan!” Mr. Knightley’s fist came crashing down upon a side table. “This miscalculation cost them the day and much more.”

“Mr. Knightley, you are not yourself,” said Miss Woodhouse. “I insist you sit down and have a cup of my father’s good wine. If you need to hear my capitulation, sir, here it is: I surrender! There is no need to continue in this manner—all to explain how a foreigner of no consequence came to live among us.”

“Emma, my dear!” cried Mrs. Weston. “That is badly done!”

“How do I offend, Mrs. Weston? As hostess, is it not my duty to see to my guests’ comfort? Why spoil Serle’s dinner with all this talk of war?”

“I fear Harriet has asked one too many questions,” Mrs. Goddard supplied. “Perhaps it would be best, dear, to refrain from posing another.”

“Not at all, Mrs. Goddard; however, in the interest of time, I will endeavor to measure my words and bring closure to the tale,” Mr. Knightley said and bowed to Miss Woodhouse. “The Duke of Cumberland’s hapless orders did indeed lose the battle at Hastenbeck. His retreat, as Mr. Weston intimated, was a matter of shame and needless casualties—among the wounded, of course, was my father.”

“Were his injuries severe, sir?” Harriet asked, unwittingly prolonging Miss Woodhouse’s vexation.

“To be sure, it never fails to astonish how my father survived that day, shattered and beaten as he was.”

“It was all due to the good doctor,” cried Mr. Woodhouse. “I may be in my dotage, but I know what I have seen and the healing I have personally experienced by that man’s hand.”

“Now, Papa, there is no need—”

“Miss Smith,” Mr. Woodhouse continued, “if only I could make you understand the consideration given to cleanliness—the rituals observed by his people. Tell them, Mr. Knightley! Tell them, for my proclivities must always appear foolish to one and all.”

“Oh no, sir!” cried Miss Bates. “That we cannot allow! Is that not so, Mama?” She enunciated loudly into her mother’s ear, though the lady was beside her. “Mr. Woodhouse says he is foolish. Such condemnation of a gentleman we hold in high esteem—why the idea…no! Never that!”

The gentleman waited until the lady had done. Harriet could only admire Mr. Knightley’s patience and solicitude, knowing that the party intended to hear the full of the story and that the gentleman was inclined to comply. In an effort to acknowledge Miss Bates’ protest, Mr. Knightley offered her a brief smile before continuing with his explanation.

“Thanks must be given to the good men who carried their injured to the nearest military outpost, marching across blackened fields littered with the remnants of the battle. When my father awoke, he found himself being prepared for the surgical theatre, such as it was. He noted a surgeon washing his hands as he moved from one patient to the next. The Prussians mocked the man, making gestures and smirking behind his back as he approached my father’s gurney. He, in fact, was not a surgeon, as my father surmised. Yosef Martsinkovsky introduced himself as the physician assigned to the British troops. The Prussians preferred to be attended by their own kind.”

“I do not understand, sir,” said Harriet. “Was he not Prussian, himself?”

“Indeed,” replied Mr. Knightley, glaring at Miss Woodhouse. “He was Prussian by birth; however, the doctor was considered a foreigner because he was an Israelite in faith.”

Read more about the good doctor, Miss Woodhouse, and Miss Smith in, “The Jews of Donwell Abbey: An Emma Vagary.” Get your copy here!

With love,