English poet, Lord Byron and Jane Austen lived through the Napoleonic Wars and the Regency era. Austen was twelve years his senior; her family moved in different social circles. It is very likely the pair never met. They were, however, distantly related by marriage…distantly, being the key word. Bryon’s great-aunt Isabella married William Musgrave. Williams’s great-uncle, the Reverend James Musgrave, was the husband of Catherine Perrot, Jane Austen’s mother’s great-aunt. Yes, the kinship was remarkedly distant; yet, interestingly enough, Austen did find a place for the Musgra(o)ve name in “Persuasion” and “The Watsons.” And, in a letter penned on Monday, September 5, 1796, Jane Austen wrote the following to her sister, Cassandra: Mr. Richard Harvey is going to be married; but as it is a great secret, and only known to half the neighborhood, you must not mention it. The lady’s name is Musgrave.

Austen was certainly familiar with Byron’s titles, such as “Oriental Tales,” “The Giaour,” and “The Corsair.” We can safely assume this is an accurate statement because Miss Anne Elliot and Captain Benwick discuss his work in “Persuasion.” And as for Byron’s recognition of Austen’s work; a recent study of Byron’s book collection revealed the poet owned first editions of “Sense and Sensibility,” “Pride and Prejudice,” and “Emma.”

Austen and Byron were the two great Romantic writers with a sense of humour.” ~Peter W Graham, Professor of English

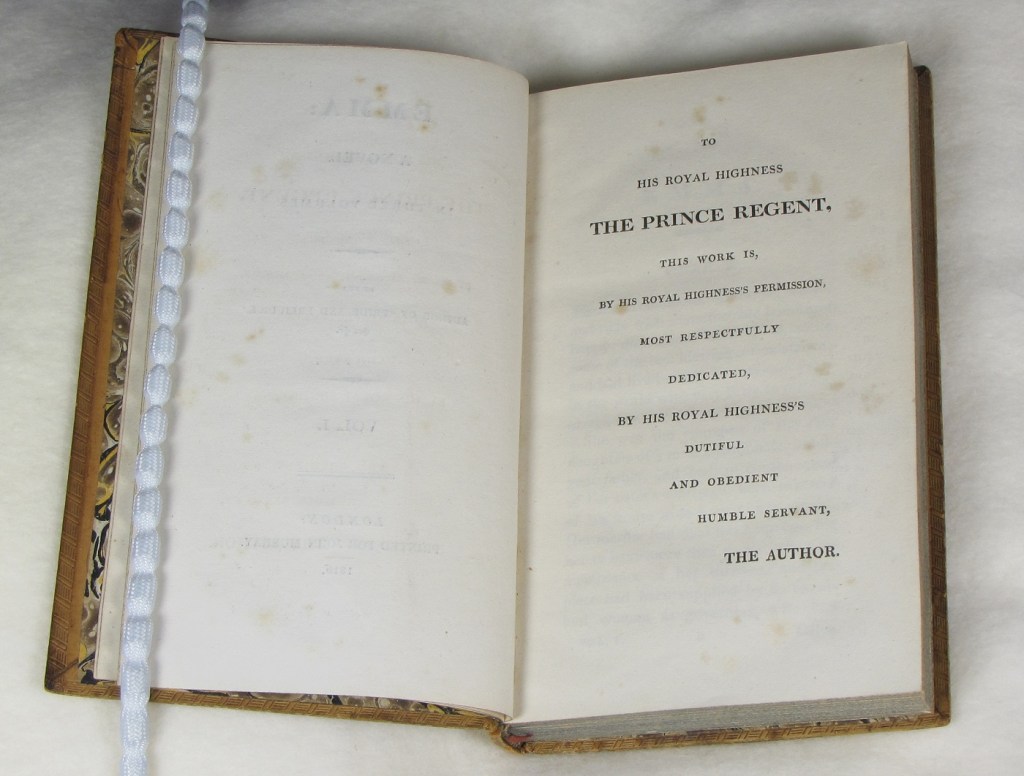

It is interesting to note that both, Austen and Byron, worked with publisher, John Murray. In a letter to Cassandra, written on Sunday, November 26, 1815, Austen stated: “I did mention the P. R. in my note to Mr. Murray; it brought me a fine compliment in return. Whether it has done any other good I do not know, but Henry thought it worth trying.”

According to the audit of Byron’s library, it was John Murray himself who provided the copy of “Emma”—complete with its dedication to the Prince Regent.

Austen’s work was published while the Romantic movement was still in its infancy. Romanticism was, partly, in response to the previous Age of Reason—the Enlightenment—and had nothing to do with romantic love. It was meant to address our “greatest mental faculty”—our imagination. It was meant to make us think about the world in its entirety, the physical and spiritual realm, and humanity’s relationship with nature. I’m not the first one to say that Austen’s Realism encompasses some of these attributes, or that her insight into human nature overlaps with Byron or Keats. In “Persuasion,” we follow Captain Wentworth’s metamorphic growth as he comes to terms with his faults and convoluted feelings. We rejoice in Captain Benwick’s transformation from a widower, wallowing in grief, to a man who rallies and loves again. We admire Miss Anne Elliot’s impassioned, internal dialogues; we understand her musings of nature and her longing for time alone to ponder and reconcile her thoughts. All attributes of Romanticism…

He is a rogue of course, but a civil one.” ~ Jane Austen

One could speculate, and rightly so, that Jane was referring to Byron in the above-mentioned quote. He was thought to be a degenerate. His own mother thought him to be a wastrel, with no care of money or duty. But Austen was not speaking of Byron. She was referring to her publisher, John Murray. “He offers £450 [for Emma]—but wants to have the copyright of M. P. & S&S included. It will end in my publishing for myself I dare say,” Austen told Cassandra in one of her many letters home.

As an independent author myself, I see that Austen shared something else with Byron. She despaired to see her work in print, but she knew her worth. In a letter dated November 30, 1815, the author wrote her niece, Fanny Knight, saying, “People are more ready to borrow & praise, than to buy—which I cannot wonder at;—but tho’ I like praise as well as anybody, I like what Edward calls pewter too.”

Byron’s association with Murray earned him nearly £20,000 over ten years, in comparison to the approximate £668 that Austen earned during her lifetime. That being said, Byron began to feel exploited by his publisher and confronted him on more than one occasion. Murray was first, and foremost, an astute businessman. Naturally, he was concerned about his customers’ tastes and opinions, especially when his famed poet attracted increasingly negative attention, both in his personal life and with his controversial causes.

I am worth any ‘forty on fair ground’ of the wretched stilted pretenders and parsons of your advertisements.” ~ Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron (1788–1824) was known for his passionate and flamboyant nature. He was a man given to romantic liaisons and extensive traveling. Sometimes, his travel plans were not of his own volition. Facing threats of personal violence—even hanging—Byron was forced to flee England on several occasions. His friendship with the Shelleys is well known, as is his love for supporting the underdog, lending his voice—and his pen—to the Greeks in their fight for freedom from the Ottoman Empire.

In May of 1813, Isaac Nathan, the son of Polish immigrants, placed an advertisement in the London Gentleman’s Magazine regarding a new project entitled, Hebrew Melodies—a collection of music well over one thousand years old. Nathan was not a newcomer to London society. He had been working as a music historian at St James’s Palace and was a singing master to Charlotte, Princess of Wales. It may have been due to this royal connection that Byron’s friend, the Honourable Douglas Kinnaird, suggested he contact the aspiring composer.

Between October 1814 and February 1815, the poet and the musician did, indeed, work together. Their first collaboration included “She Walks in Beauty”—a poem that predated their partnership, although Nathan married this work to a known melody used for Adon Olam, a song for the Sabbath morning service. He set the first volume of Byron’s poems to music for voice and piano in April 1815— presumably for the Pesach (Passover) holiday which was commemorated that year from April 24th through May 2nd. It was printed by T. Davidson of Lombard Street and published by John Murray—and dedicated to the Princess by royal permission. Before absconding from England, Byron bestowed the copyright of the publication to Nathan.

Nathan sent his partner a gift with the following note: My Lord, I cannot deny myself the pleasure of sending your Lordship some holy biscuits, commonly called unleavened bread, and denominated by the Nazarites Motsas, better known in this enlightened age by the epithet Passover cakes; and as a certain angel by his presence, ensured the safety of a whole nation, may the same guardian spirit pass with your Lordship to that land where the fates may have decreed you to sojourn for a while.

The following response was received: Piccadilly Terrace, Tuesday Evening~ My dear Nathan, I have to acknowledge the receipt of your very seasonable bequest, which I duly appreciate; the unleavened bread shall certainly accompany me on my pilgrimage; and, with a full reliance on their efficacy, the motsas shall be to me a charm against the destroying Angel wherever I may sojourn; his serene highness, however will, I hope, be polite enough to keep at desirable distance from my person, without the necessity of besmearing my door posts or upper lintels with the blood of any animal. With many thanks for your kind attention, believe me, my dear Nathan, yours very truly, BYRON

Not all of the poems in Hebrew Melodies are specifically Jewish in theme, but they do express sympathy for the plight of the Jews. Due to his enthusiasm for supporting “foreign liberation struggles,” the poet’s teaming up with Isaac Nathan may not have been much of a surprise to society. George Canning, a British statesman, once said that Byron was, “a steady patriot of the world alone, the friend of every country but his own.” Whether he meant to be, or not, he was immensely popular with Zionists. In fact, Anglo Jews said if their political organization had only begun a few decades earlier, Lord Byron may have been “its champion.”

Zionist poetry owes more to Byron than to any other Gentile poet.” ~ Nahum Sokolow

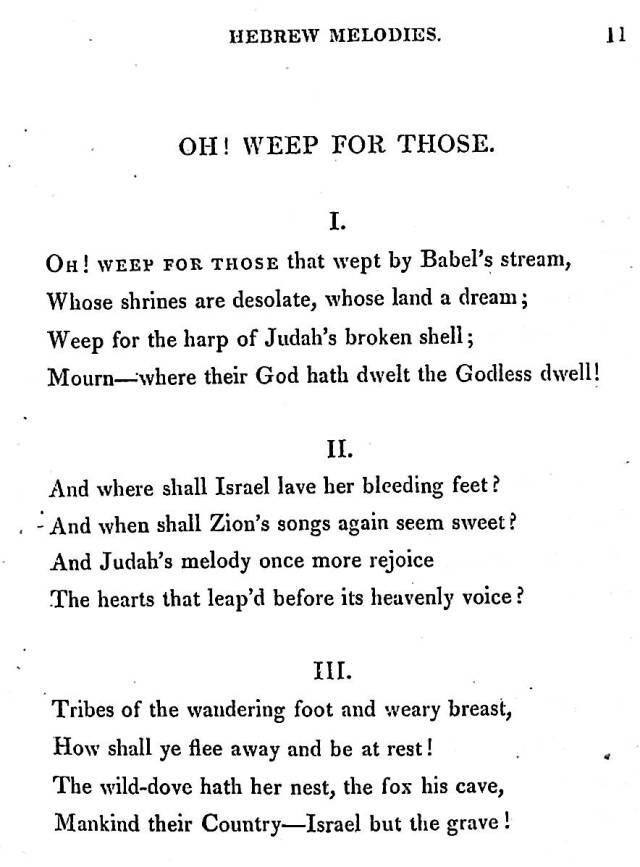

According to those in the know, there is no evidence that Byron “saw the Jewish tragedy as amenable to a political solution.” Yet, the poem “Oh, Weep For Those!” laments that the Jews have no home. Listen to the melody here

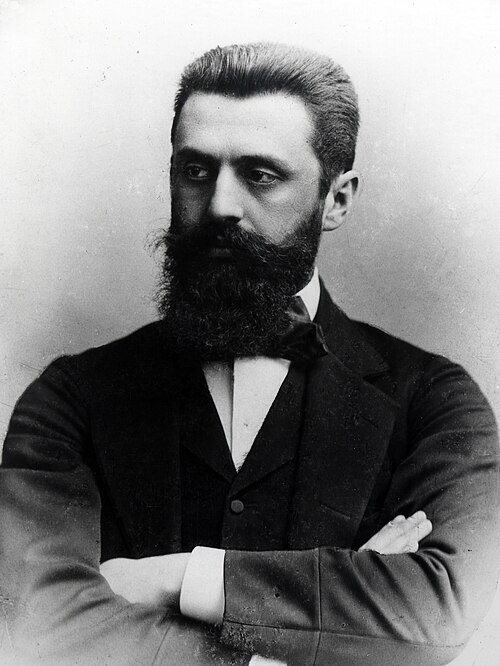

The work was later translated into Hebrew by J.L. Gordon as Zemirot Yisrael (1884) and into Yiddish by Nathan Horowitz (1926). Thanks to these translations, settlers of the First Aliyah (1881 – 1903) sang, “Oh! Weep for Those!” to their own—improvised—tune. Theodor Herzl, the father of modern Zionism, may have even quoted it at the Second Zionist Congress 1898.

Byron’s influence on his own generation of Russians surpassed that of Tolstoy. ~ Vladimir Jabotinsky

Having received such accolades and support from Jewish leaders, one would think that Lord Byron was Klal Israel’s chief advocate. That, sadly, was not the case. Byron’s main interest was championing Greek independence and, in that cause, Greek Christians did not favor their Jewish neighbors. In 1821, all one thousand Jewish inhabitants were massacred in Tripolitsa, along with their Muslims counterparts. Byron did not repudiate the action. A few years later, in 1823, Byron wrote, “The Age of Bronze”—a poem that raged against land barons, including Anglo Jews such as Rothschilds, as “living on the blood, sweat, and tear-wrung millions.” It is said that Byron was well aware of the flaws in some of his philosophies and causes. His willingness to look past them is the dark side of Romanticism, where reason is completely overwhelmed by Man’s ability to do evil.

That said, Herzl, and many of his followers, believed that Zionism owed a debt of gratitude to Romanticism. These authors provided the inspiration—the impetus—for Jews finally returning to their homeland. It seems that, despite religious, political, or geographic differences, Lord Byron remained popular with Jewish readers. Perhaps it was because they could identify with the man’s passionate nature and questioning mind.

The Romantics encouraged us to feel the full spectrum and intensity of human emotion: joy, grief, love, anger, veneration, jealousy, pride… They asked us to observe an object of beauty, or empathize with someone’s pain, in order to transcended rational thought; and in doing so, to connect with the essence of humanity.

In this day and age, where we text and post and rage without thought of the pain we may cause—or the Truth we may be concealing—I wonder if we shouldn’t take a page from the Romantics, and connect to something greater than ourselves. Just the ramblings of an Independent Author…

With love,

What a lovely and informative post. Thanks. It’s great to see a post emphasizing the politics of Byron and the Romantics and the true nature of the Romantic movement. RB

>

I’m glad you enjoyed it! Fascinating information, isn’t it?