It was recently pointed out to me that I was born in the “early 1900s.”

Wait! What?

You could have knocked me over with Mr. Carson’s Bowler hat…

Obviously, I know my own birthday—I know that I’m considered a “baby boomer”— but, come on now!

Some of you are from my generation. How does that statement strike you? The “early 1900s” gives Downton Abbey vibes, doesn’t it? Not hip-hugger bell bottoms, olive green and orange kitchens, or mountain-high platform shoes!

That being said, I have to admit the speaker was right. I was born in 1962, in the middle of what is known as the “Mid-Century Modern” period; and, while I typically gravitate to the late Victorian or early Edwardian eras for entertainment, many others think of Mad Men, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, or Call the Midwife. That’s why when author, Alina Adams told me about her new release, I thought she’d be a fabulous guest host. Along with her personal family history and immigrant experience, her professional background lends itself perfectly to this complex and conflicted era. That’s why I am honored to welcome Alina back to the blog!

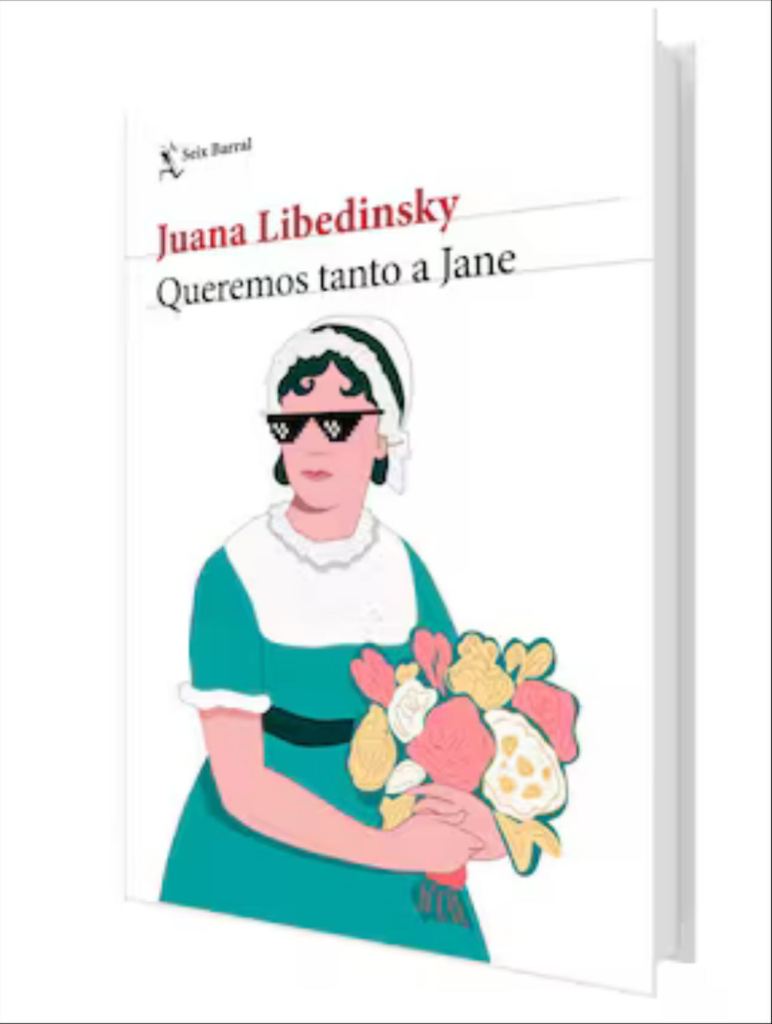

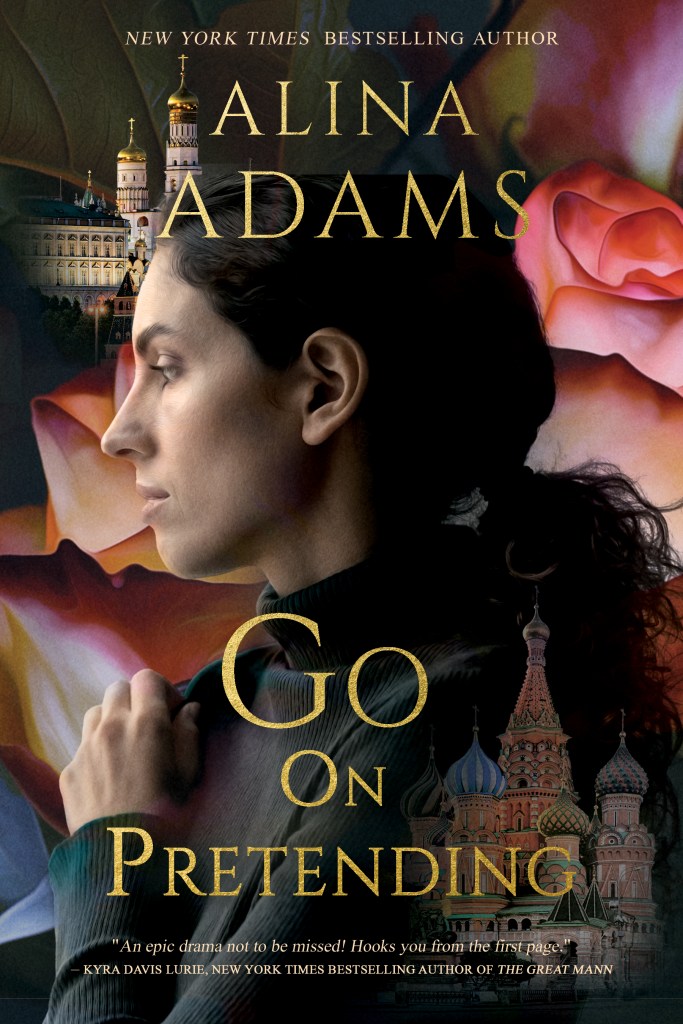

We have previously collaborated, as some of you may recall, such as in this author’s interview promoting her book The Nesting Dolls, but today, Alina will be sharing an excerpt of her latest novel, “Go On Pretending.” It’s scheduled to be released on May 1, 2025.

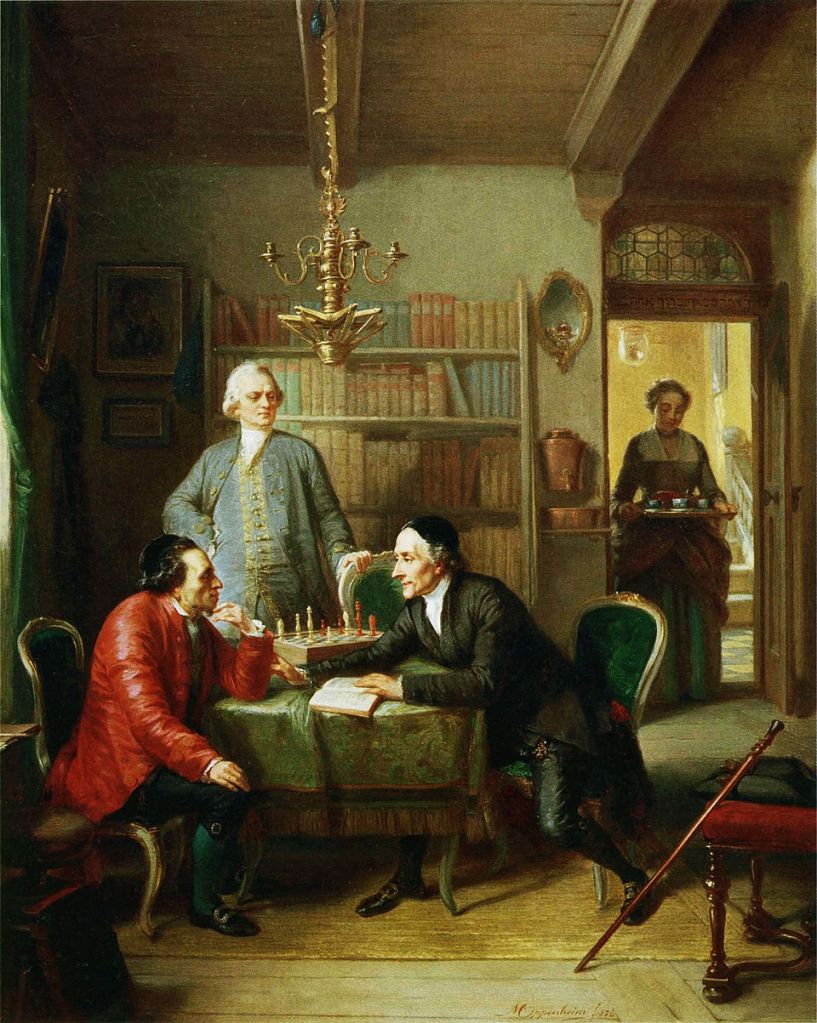

I first discovered the author when I read The Fictitious Marquis. The Romance Writers of America named this Jewish Regency Romance the first Own-Voices Jewish historical; however, along with being a New York Times best-selling author, Alina is a soap opera industry insider and a pioneer in online storytelling and continuing drama. Throughout her career, Alina has worked as a television writer, researcher, website producer, content producer, and creative director. So without further ado—ladies and gentleman:

ALINA ADAMS!

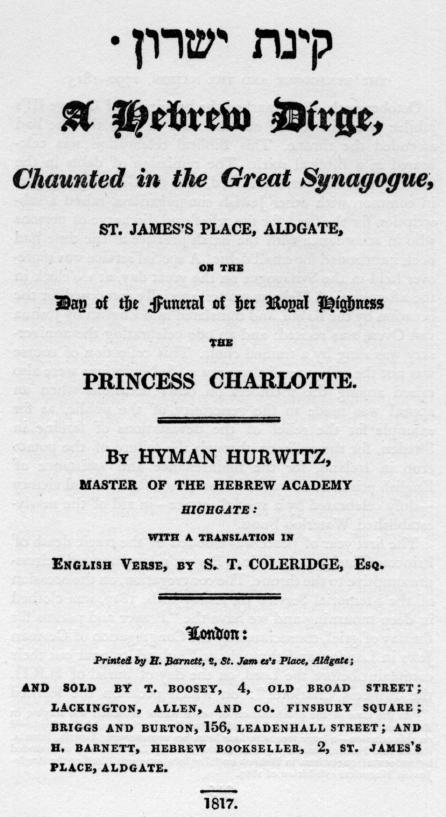

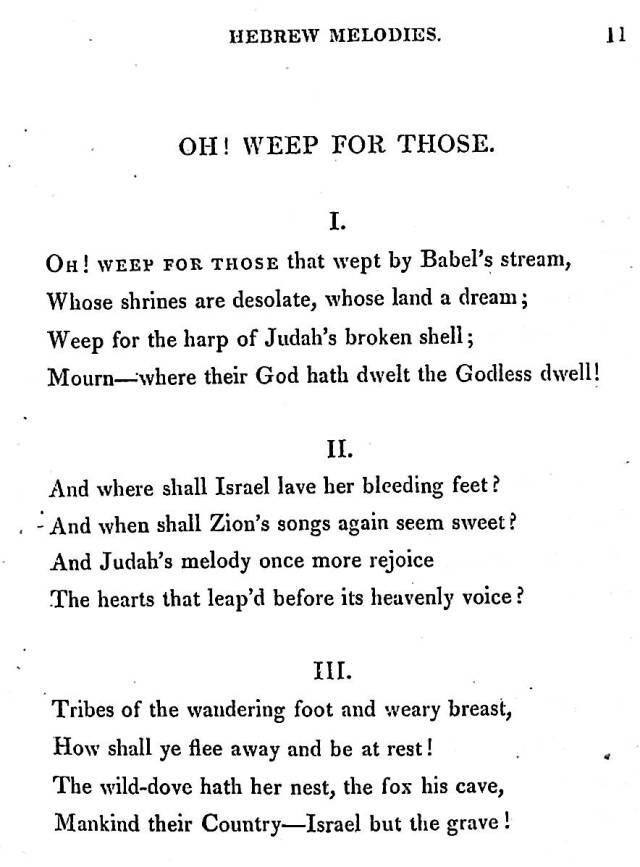

I realize this blog is usually about romance in the Regency, Victorian and Edwardian eras (with some sprinkling of Jews), but I’m hoping readers will indulge me just a little for this guest post. I promise there will still be romance! Only it will be more modern. The 1950s, to be precise. So not too modern. And it will still feature romance. Plus some Shakespeare, to boot! (Which, I realize is Elizabethean… so… closer.) But there will definitely be Jews!

In fair New York City, where we set out scene, Rose Janowitz (that’s the definitely Jewish part) has just started working for the radio soap opera “Guiding Light” and it’s brilliant, mercurial creator, Irna Phillips, when she is forced to confront the drama, intrigue and romance of her own life – or lack thereof. What happens next is not at all what anyone expected…

There were llama droppings on the marble stairs.

Rose couldn’t have been happier.

“Props!” she shouted, leading to a chorus of chuckles and groans. The studio where they staged The Guiding Light for fifteen minutes live every weekday, year round, also broadcast periodic, experimental television programs. Said programs featured a disproportionate number of animal acts. As the building had no elevator, the cast, sets and assorted creatures arrived via marble staircase. This not only made a clatter – while they broadcast, Rose stationed boys at the top and bottom to stop anyone from interrupting; an aspect of Rose’s job Irna had neglected to mention – but also proved a magnet for fecal droppings of many sizes and textures. There was an ongoing building argument about which department’s responsibility clean-up fell under. Most recently, it had been dumped on – pardon the expression – props. Hence, Rose’s call.

While such matters, technically, did not fall under her job description, Rose didn’t mind. She was happy to do whatever it took to keep the wheels of production churning. Because, as she’d promised Irna, the show came first. Everybody from Network Head to actors with a single line, not to mention the sound effects crew, the director and engineers, put their personal needs on the back burner and rallied to ensure their product was the best it could be from the moment the organ announced its histrionic beginning, until the music adroitly faded “until next time.” Rose would have expected to experience the height of worker solidarity at proudly socialist WEVD. It turned out, though, that there was nothing like money to be made to get everybody enthusiastically rowing in the same direction.

Money, of course, was also the source of some of their greatest conflicts. Not among the staff, but among those who created the shows and those who controlled them. Sponsors loved getting into the act, demanding characters use their products, orate about using their products, and marvel at the convenience and thrift of using their products. Irna was a wizard at scripting heart-clenching drama to take place amidst a variety of cleaning supplies. If a villain wasn’t being threatened to have his mouth washed out with soap (only one brand would do!), then the heroine was hurrying to get her laundry done before her husband arrived home and learned she’d been out all day, engaging in who knows what mischief. How lucky she was that this brand of detergent took half the time for twice the results!

Their bigger problems stemmed from all that they weren’t allowed to do by Standards and Practices. According to “daytime morality,” good men and women could not smoke. This infuriated Irna, who saw thousands of dollars in potential sponsorship monies wafting away like, well, smoke. It was Rose who came up with having the bad characters be the smokers, but of having the good ones constantly remark on it. “Go, and take your (brand of) cigarettes with you!” and “I knew you’d been there. I could smell your (brand of) cigarette the second I arrived!” That way, they wouldn’t be going against the censors, but the product would still be associated with the voices of heroes and heroines.

They faced the same obstacles with alcohol. Even beer and sherry were off limits. Tea or coffee were the mandated beverages of choice, no matter what the crises. (They could always select from hot or iced, in case anyone complained of feeling creatively shackled.) Inspired by prohibition, Rose suggested to Irna that she write any drinking as either religious or medicinal. When Rose submitted that having Jewish characters would make a sip on Friday a directive from God Himself – what pious censor could deny that? – she actually pried a smile out of her redoubtable boss.

Their biggest problem, however, was sex. They couldn’t show it. This was radio, not the movies. They couldn’t speak of it. This was radio, not… the bible. (Irna had chortled at that one, too, which was the biggest compliment Rose could hope for.) On The Romance Of Helen Trent, one of the few radio soaps not created by Irna, where the titular heroine had been proving that “romance can begin at thirty-five” for seventeen years; while managing to remain thirty-five – they spoke of the “emotional understanding” that could only come with marriage. And not a second before. They meant sex. Everyone knew they meant sex. But no one was allowed to say it. Irna gave notice she wasn’t going to adopt that awkward turn of phrase for her own shows.

So, on The Guiding Light, characters begged each other to “hold me and never let me go.” They embraced. Quite a bit. They stared into each other’s eyes. Sometimes from one day to the next. And then they somehow ended up pregnant. Viewers filled in the gaps on their own.

Rose wished she could do the same. She’d told Irna the truth when she answered she wasn’t married. But she’d never confirmed the implicit promise that she never would be. She’d like to be. No matter how many times Mama told Rose she’d ruined whatever chance she’d had – what man would want her after what she’d done, what woman would want a man who would; it was quite the recursive question – Rose never quite managed to give up hope. She was a year short of thirty now. If Helent Trent could “find romance” at an even more decrepit age, why not Rose Janowitz?

She spent her days surrounded by men. For a woman’s genre, daytime drama – save Irna – was suspiciously dominated by men. Men at Procter & Gamble, men at the network, men at the advertising agency, men in the production booth, men on the studio floor. There were men in tailored suits and men in shirtsleeves. Men in fedoras and men in caps. Men wearing the latest No. 89 by Floris cologne, and men who smelled of the Ivory P&G gifted each employee at Christmastime. There were men wherever Rose looked. So why was she still alone?

Naturally, a majority of those men were married. Rose wasn’t ready to go the mistress route yet – though she knew Irna had a stable of such philanderers in her life. Irna preferred doctors and lawyers, just like on her shows. If Rose were twenty, the pickings might have been broader. But men her age were interested in younger women. And older men were either divorced – which came with children and alimony… and bitterness – or… well, Mama said Rose was picky. As tall as she was, she had to accept that some men would be shorter. As opinionated as she was, she had to accept that silence could be golden. And certainly she must never talk about how much money she was making. No man would stand to be emasculated in such a manner. Yet, after all that, remember, he had to also be Jewish. Anything less would be unthinkable.

The worst part was, Mama was right. Rose was too picky. She could put up with short. She could put up with poor. She could put up with old. The one thing she could not put up with was: boring. Compared to the hustle, bustle, constant crises and close calls of production, the conversation proffered by the majority of men Rose met for dinner dates left much to be desired. Mama said it was because Rose challenged them. Rose should be sitting quietly and listening. Yes, even when the men were wrong. Especially when they were wrong. A good man, Mama lectured, didn’t expect the woman across from him to know more about a given subject than he did. And he certainly didn’t appreciate her demonstrating it. When a man waxed poetic about a film he’d seen, he didn’t need Rose breaking down the dialogue and scene structure. When he talked facts and figures about his job, he didn’t need to know that Rose also oversaw a budget – and it was greater than his. And he definitely had no interest in anything she had to say about politics! Rose found the men she stepped out with boring. She could only imagine what they thought about her.

Luckily, she had very little time to dwell on it. Irna lived up to her promise. She kept Rose so preoccupied, the only love lives Rose agonized over were Bill and Bertha “Bert” Bauer as they battled that floozy, Gloria, and whether widowed reporter Joe should choose Nurse Peggy, whom his children preferred, or ex-jailbird Meta, who made Joe’s heart flutter. Irna was thinking bigger than radio. She’d already produced one television soap-opera, These Are My Children, which sputtered out after less than a month of episodes on NBC. Yet Irna remained convinced the fledgling medium was her serials’ future. To that end, she was battling to convince Procter & Gamble to resettle The Guiding Light on the small screen. To assuage their doubts about its viability, Irna used her own money to produce a pilot. When it failed to convince her sponsors, she set to work on a second one.

This meant Irna had less time for the radio version. Outside of writing, which Irna still guarded ferociously, the bulk of responsibilities were now Rose’s. Rose raced from advertiser meeting to rehearsal to casting session. When the latter was plunked in her lap, Rose switched all auditions to the telephone. It allowed her to sift through paperwork without the actor noticing her distraction and getting – rightfully – offended. It also kept Rose from basing her decisions on appearance. It was difficult to picture a dashing, romantic leading man when the applicant was balding and barely came up to Rose’s chest, or an ingenue when the lady reading for the part looked more appropriate for grand opera. Since all that mattered was how they sounded, Rose holding auditions over the phone was more likely to yield unprejudiced results. Which was what was best for the show. Because the show always came first.

On the schedule for today were tryouts for a new role, that of ne-er-do-well Edmund Bard, who’d be coming to town to set every young and not so young lady’s heart aflame, toy with them mercilessly, then be revealed as the illegitimate son of a pillar of the community. It was a fun, juicy role, and Rose was looking forward to hearing her candidates’ takes on it.

The first six proved a disappointment. They were playing it too evil right from the start. There was no tension, no surprise, nothing to reveal or learn. Rose couldn’t imagine listeners at home not seeing right through the literal bastard and wondering why the women of The Guiding Light couldn’t do so, as well.

For the seventh applicant, Rose didn’t even glance at his name until after he’d been speaking for almost a minute. She didn’t even listen to the words – she’d heard them so many times – until she realized that – what was his name, now? Cain… Jonas Cain – was offering a completely different interpretation from the men who’d preceded him. Where they’d snarled, he purred. Where they’d bellowed, he murmured. Where they’d insisted on seduction, he made the listener want to be seduced. No, he made the listener ache to be.

“Mr… Cain,” Rose needed to clear her throat, lest her voice crack.

“Yes, Miss Janowitz?” His speaking voice was the same as his auditioning voice. Which meant he was either always on, or always himself.

“That was… that was quite… good.”

“I thank you for saying so.” Yes, he was definitely always… something. Impossible to believe he didn’t realize precisely what effect his speaking voice had on the listener. And that he wielded it for all it could do for him. Rose didn’t blame him. She’d do the same in his position.

“May I ask what inspired your take on this character? It’s so different from how every other actor saw him.”

“Is it now?”

A drawl? A bass clarinet? A full-throated pipe organ? Just what was it about this man’s voice that made Rose vibrate from hip-bone to hip-bone as surely as if he’d plucked a string, like Rose might melt through her desk-chair, dissolving towards the carpet.

“Yes.” This time, she swallowed instead of coughing. Hardly less obvious.

“Well, it’s obviously Shakespeare, isn’t it?”

“I’m sorry, what?”

“Edmund Bard?” His laugh rolled in like a fog diffusing throughout her senses. “You gave the whole game away right there. He’s Edmund the Bastard from King Lear.” Jonas quoted, “To both these sisters have I sworn my love; each jealous of the other, as the stung are of the adder, which of them shall I take?” When Rose didn’t reply quickly enough; primarily because she’d run out of coughs and gulps and felt pressed to come up with an alternative; speaking was out of the question, his confidence wavered. “Did I get it wrong, then? How terribly embarrassing.”

“No.” Rose found her voice, because his had briefly tottered. “You’re one hundred percent correct. When Irna – Miss Phillips – when she told me about the character, I suggested the name. As sort of a little joke between the two of us.”

“Ah! So you’re the Shakespearean scholar.”

“Hardly!” Her snort was instinctive. If utterly unladylike.

“It was precisely the guidance I required to understand this man. He commits villainous acts, seducing married women, attempting to murder his father and brother, but he does not see himself as the villain. After being cast aside for an accident of birth, he feels righteously justified to, as they say: top the legitimate. I grow; I prosper: Now, gods, stand up for bastards! Surely, a sentiment we’ve all experienced. Whether or not we’d admit it.”

Was that the moment Rose fell in love with him? In later years, decades, centuries, that was the seed she traced it all back to. The moment when Jonas Cain – with a pinch of help from William Shakespeare – put words, put poetry, to the feelings Rose had been pressing down her entire life. Because the one time she’d let them roam free, she’d ruined everything.

She’d read those words. If she hadn’t read King Lear she wouldn’t have known of Edmund, and if she hadn’t known of Edmund, she never would have suggested that name to Irna. And if she’d never suggested that name to Irna, what would Rose and Mr. Cain be speaking about now?

She’d read those words. But she’d never heard them outside a well-meaning college professor who made as apt an Edmund as she did a Juliet. Rose had read the words, she’d heard the words recited. She’d never realized they were about her until they came undulating over the phone line at her office on the East Side of Manhattan.

Rose might have fallen in love with Jonas then and there. But the only thing she said was, “You’ve got the job.”

Rose sent the standard contract to Mr. Cain’s agent, perplexed when it was returned promptly, without a change. She wondered if her new employee had inexpert representation – it was an unknown to her agency – or whether they were desperate to see the document counter- signed before… what?

What could they be hiding? She’d heard the voice. The voice was all that mattered. The worst Rose could conceive of was Jonas Cain might be a pseudonym, and he was employed on another show which forbade him from performing on competing programs. But Rose listened to a lot of radio. She felt certain that, if she’d heard his voice before, she’d have proven incapable of forgetting it.

On the morning Jonas Cain was scheduled to come in for his first broadcast, Rose made a point of not dressing any differently. It was just another day. No longer did a chic autumn coat cost more than her weekly salary. Thanks to Irna, Rose could afford a closet full of crepe and taffeta tunic dresses with their touted slenderizing waists and straight three-gore skirts. She’d paid extra to have the lapels and pockets dotted in rhinestones, as per the current fashion. The sole reason Rose chose the lightweight green over the navy fine-ribbed was because the day was shaping up warm. She didn’t want to overheat. It wasn’t because the white jabot of the latter made Rose appear older – she saved those for meetings with the sponsors – while the overbodice of the former brought out the hazel in her otherwise dull brown eyes. A pair of black Capezios with sharply pointed toe-tips completed the ensemble. Rose opted for flatties. No reason to appear any taller than she needed to.

Because one thing that Rose had already braced herself for was the possibility of Jonas Cain being short. She had no idea why a disproportionate number of deep-voiced men seemed to be challenged in the height – and follicle – department. Maybe a compressed entity was vital to generate such a profound resonance? Rose told herself she didn’t wish to intimidate Mr. Cain by towering over him. Not on his first day.

“Jonas Cain is…” the voice of the unspeakably competent assistant Rose met the day of her interview and now knew to be named Hazel, that she was twenty-four years old, working to pay her husband, Ike’s, way through medical school, counting the days until she could quit and just be a normal wife and, hopefully soon, mother to a brood of baby Ikes, echoed through the intercom on Rose’s desk, “… he’s here.” In later years, Rose would wonder if her taking heed of the unusually long pause in Hazel’s announcement might have changed anything. Would she have been better prepared for what was to come? Might she have circumvented it in some way? Did she wish she had? Would she have wanted it any other way?

“Send him in,” Rose chirped, oblivious to the message Hazel was trying to transmit.

“How do you do, Miss Janowitz? Jonas Cain, at your service.”

Rose had been in the process of rising to greet him. She’d just pressed her palms into the desktop, which came in handy when she nearly lurched forward, only stopping herself from plunging face first by the fact that her arms were already locked at the elbows.

She’d braced herself for Jonas Cain being short. She’d braced herself for him being ancient, him being a child half her age. She’d braced herself for his having a face Mama called “perfect for radio,” and a host of other deficiencies, as well.

She hadn’t braced herself for him being a Negro.

For soap operas, viewers had to tune in tomorrow to find out “what happens next.”

For readers, though, here is the rest of the story….

To pre-order “Go On Pretending,” please click on the link: https://www.historythroughfiction.com/go-on-pretending

Thank you!