What’s a nice, Jewish girl to do when the vast majority of the population is snuggling by a roaring fire with Hallmark movies and Dickens’ classics? Well, I’ll tell you. If that nice, Jewish girl happens to write Jane Austen Fan Fiction, she may share a little bit of history on the Jewish Festival of Lights. She may also share a snippet or two from her novels to illustrate the true meaning of the season.

I’ll stop writing in the third person now…

I realize that we’re still in the fall season here in the northern hemisphere, and there are other holidays to commemorate before we head into the darkest part of the year. However, I felt that this post was well-timed as the Jewish community has been experiencing “the darkest part of the year” since the horrific events of October 7, 2023. To date, we are still waiting for all of our hostages to be returned.

In just a few weeks’ time, we will begin preparing our latkes and sufgenyiot for our holiday meals. Dreidels and coins will decorate our tables too. The battles that were won, the significance of the dreidels and coins, the reasons why we eat fried foods—or, even dairy—are all well documented; you can read more about it here.

A Great Miracle Happened There!

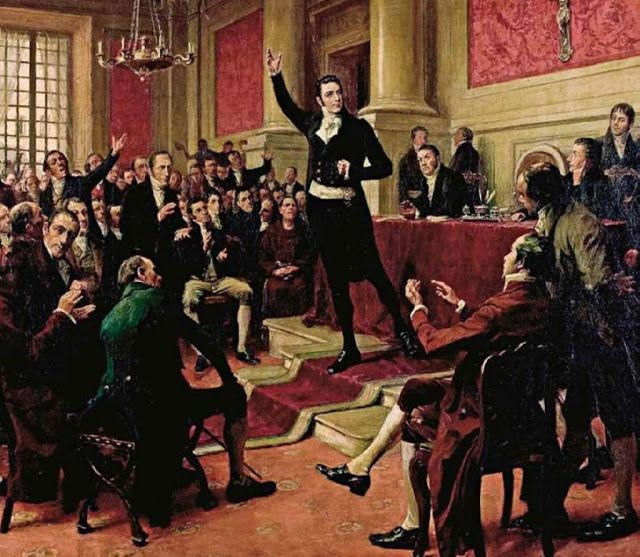

Chanukah tells the tale of an impossible victory over the mighty Greek army in the 2nd century. This was a true, historical event—a terrestrial miracle that serves as reminder that Jerusalem and the Temple were lost and recovered due to the Maccabean revolt against tyranny and forced assimilation.

The second miracle of the holiday, however, is not so tangible. It is the story of how a small vial of sanctified oil was able to keep the Temple’s menorah lit for eight days and nights. The flames of the chanukkiah (the Chanukah menorah) speak to faith (emunah) and trust (bitachon). In celebrating this holiday, we are encouraged to emulate these characteristics, even when the world is enveloped in darkness—even when we are heartbroken and our spirits are brought low. As an author of Jane Austen Fan Fiction (J.A.F.F.), I wanted to highlight these themes, and show how I have attempted to underscore their importance in my J.A.F.F. or Jewish Austen Fan Fiction.

חג חנוכה שמח

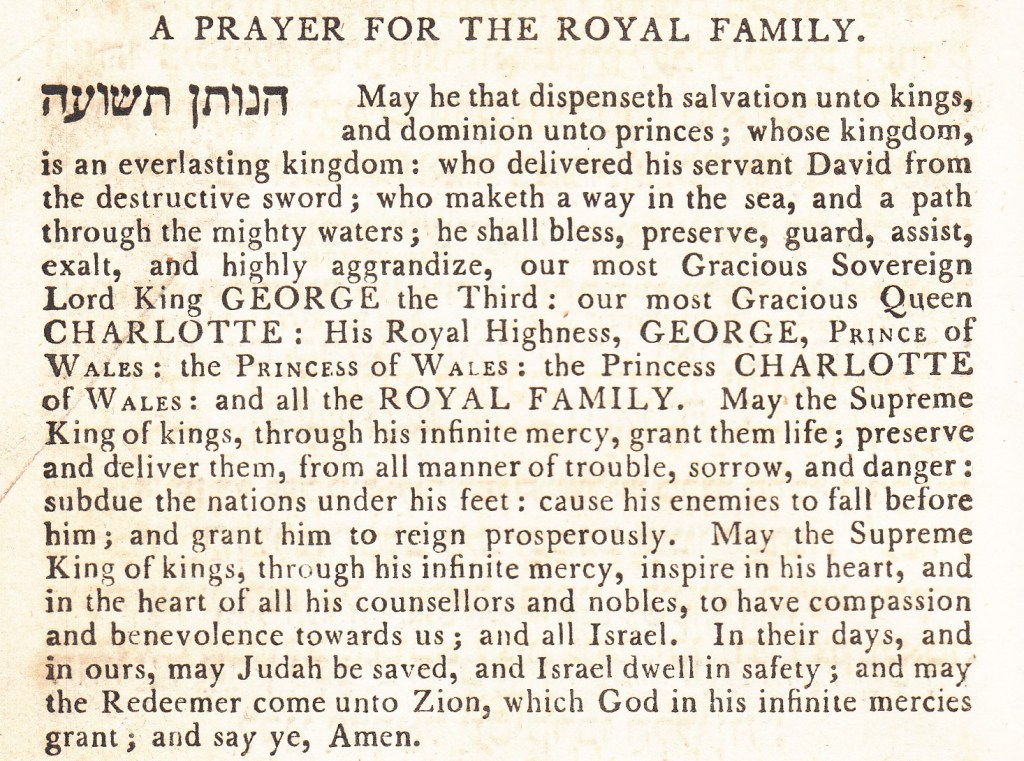

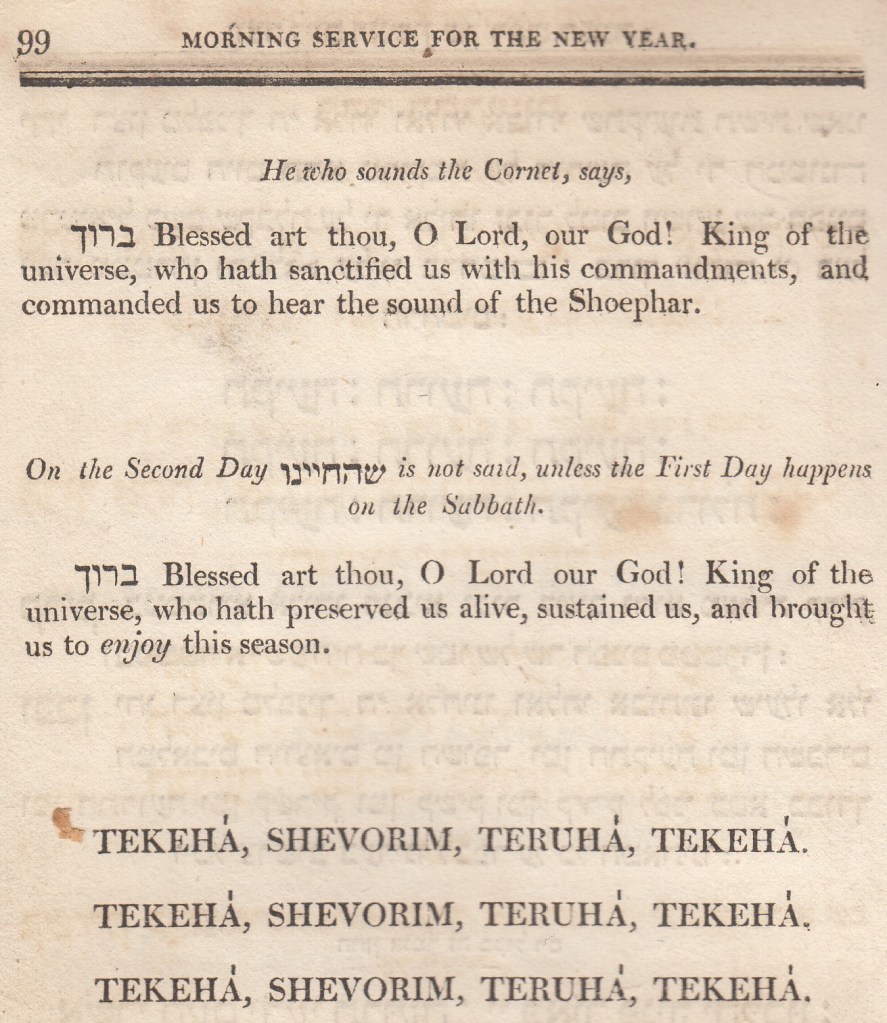

The Hebrew greeting noted above is transliterated as Chag Chanukah Sameach, which means Happy Chanukah Holiday. No doubt, you have seen many different spellings of Chanukah, Hanukkah, even Januca—as it is written in Spanish. While many people call it a minor holiday—it’s not included in the Torah (the Five Books of Moses a.k.a. Pentateuch)—it has been commemorated by Jews for centuries… even in Jane Austen’s time.

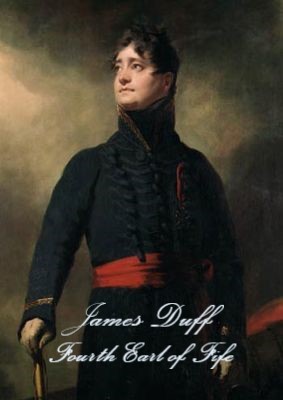

On November 5, 1817, just prior to the holiday season in Regency England, tragedy struck. Princess Charlotte, the Prince Regent’s daughter, and heiress-presumptive to the throne, died after giving birth to a still-born son. The whole of the empire had been following this pregnancy; Charlotte was a favorite amongst the British people and her marriage to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha had been a love match. The public were besotted by their fairy-tale union and by what the couple’s future foretold; however, Charlotte’s death at the age of twenty-one threw a stunned nation into deep mourning.

The outpour of grief for the young woman and her child was said to be unprecedented. Mourning protocols were highly respected during this period of time. Needless to say, when the deceased was a member of the royal family, and a favorite at that, the public were united in their sorrow.

“It really was as though every household throughout Great Britain had lost a favourite child.” ~ Henry Brougham

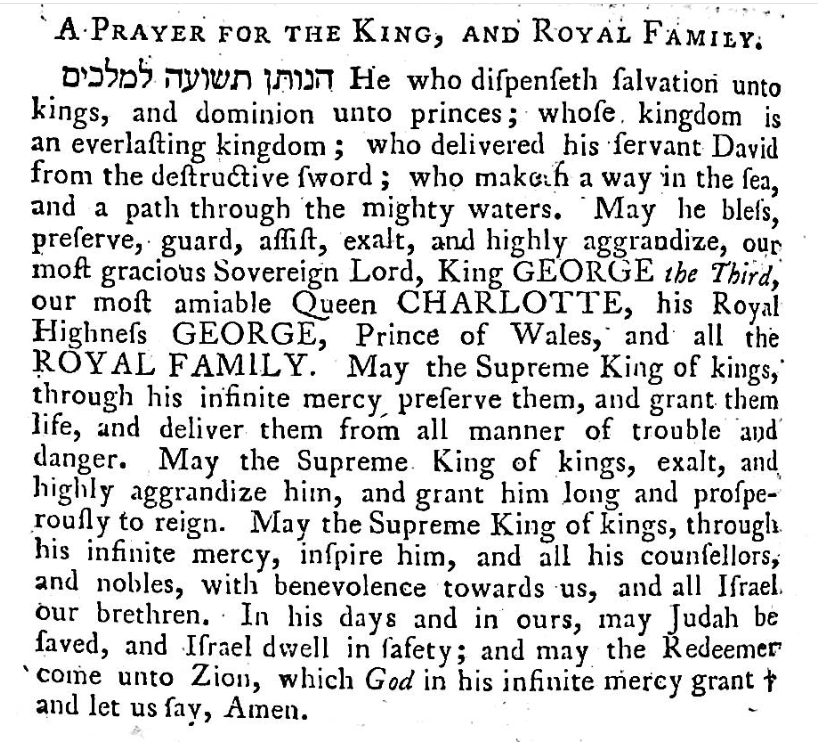

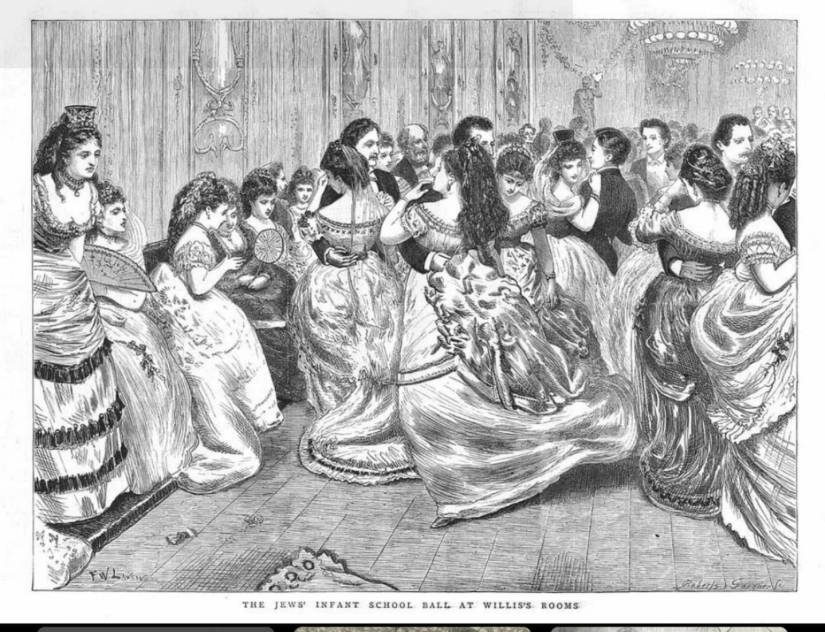

The Royal Exchange, the Law Courts, merchants, tradesmen, and schools closed down. There was a shortage of black cloth, as everyone wished to show their respect by wearing mourning armbands. Jane Austen and her family would have participated in these rituals. Naturally, the Jewish community aligned themselves with their compatriots.

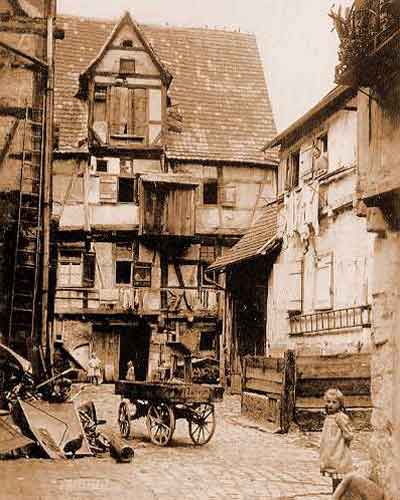

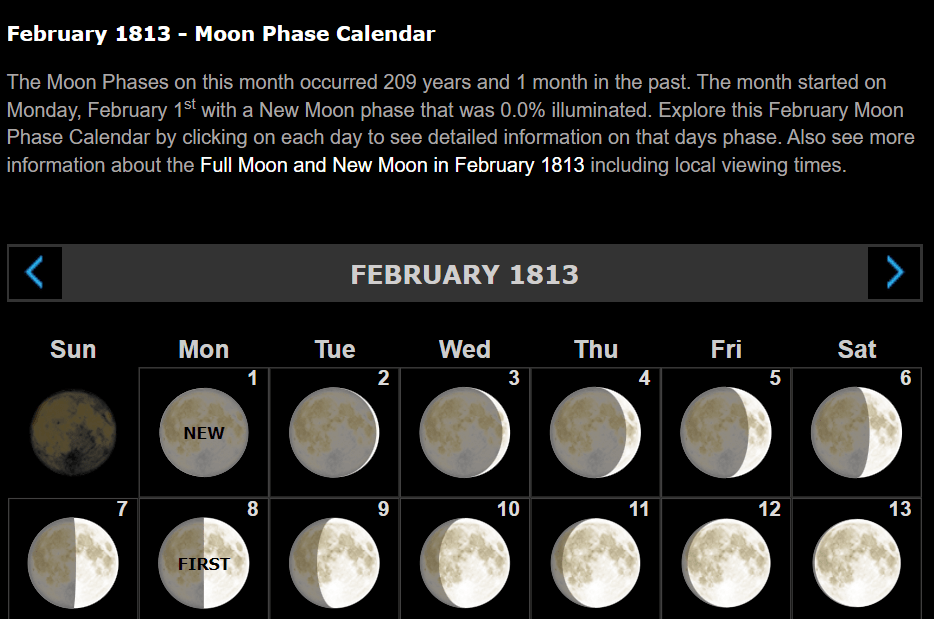

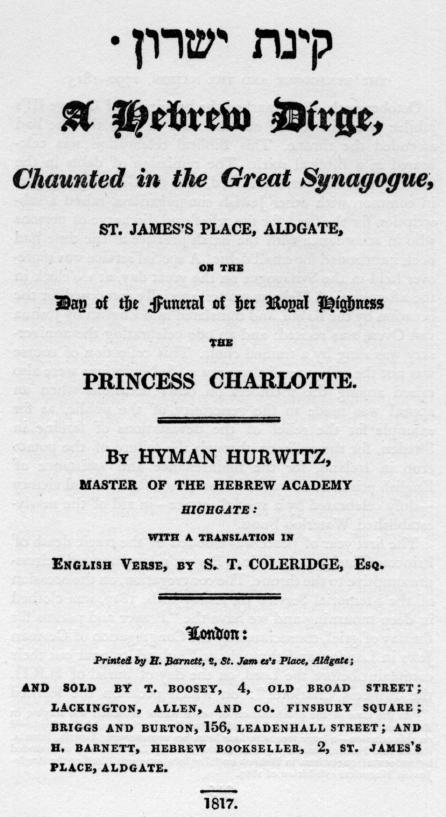

Per the Gregorian calendar, November 19, 1817 correlated to the Hebrew date of the 10th of Kislev, 5578. Prior to the tragic news, Jewish congregations throughout the land would have been planning for the upcoming Festival of Lights; Chanukah falls on the 25th of Kislev. However, all such preparations came to a halt upon receiving the sorrowful news.

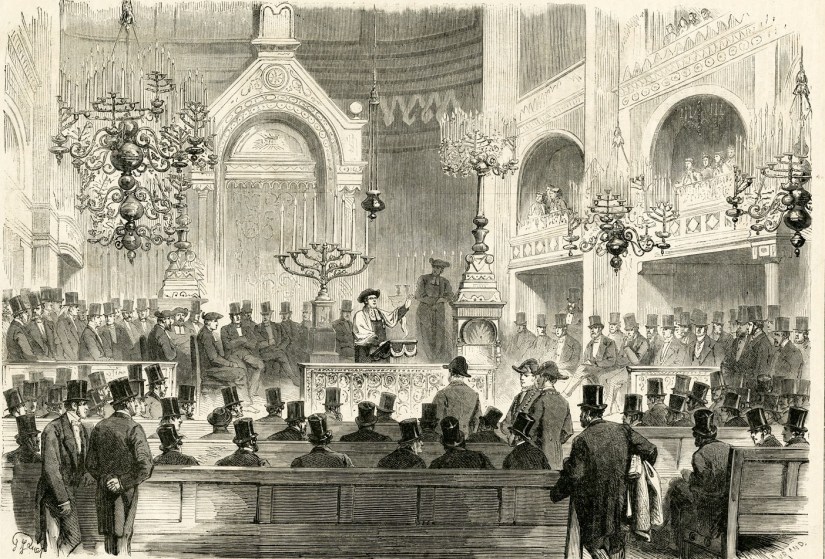

On November 19th, a memorial service was organized for “prayer and psalms for the day of grief” in the Great Synagogue, St. James’s Place. Congregants were allowed to “pour out their complaint before the Lord, on the day of burial of H.R.H. the Princess Charlotte.”

Hyman Hurwitz, the head master of a “fashionable” Jewish school at Highgate, composed Mourn the Bright Rose: A Hebrew Dirge and it was chanted to the tune of a well-known composition, typically recited on the Ninth of Av—a tragic and solemn occasion on the Hebrew calendar.

Rabbi Tobias Goodman, known amongst his congregation as Reb Tuvya, spoke on “the universally regretted death of the most illustrious Princess Charlotte of Wales and Saxe-Coburg.” Rabbi Goodman quoted Ecclesiastes in saying, “A good name is better than precious ointment, and the day of death than the day of one’s birth. It is better to go to the house of mourning than to the house of feasting, for that is the end of all men; and the living will lay it to his heart.”

I don’t know what followed. Perhaps the rabbi repeated the time-honored phrase, “Od lo avda tikvatienu,” (our hope is not extinguished) capturing the essence of Chanukah. He might have referenced Joseph and his brothers in Egypt, by saying: “Praiseworthy is he who places his faith in God” and “Remember I was with you.” Whatever else was said that day, I can only imagine the congregation went home with words of consolation and hope.

Jane Austen said, “My characters shall have, after a little trouble, all that they desire.” That speaks to her genius, of course. As in any book, there needs to be an arc to the storyline. There needs to be growth. The heroine must face her fears and rise above the obstacles placed in her path.

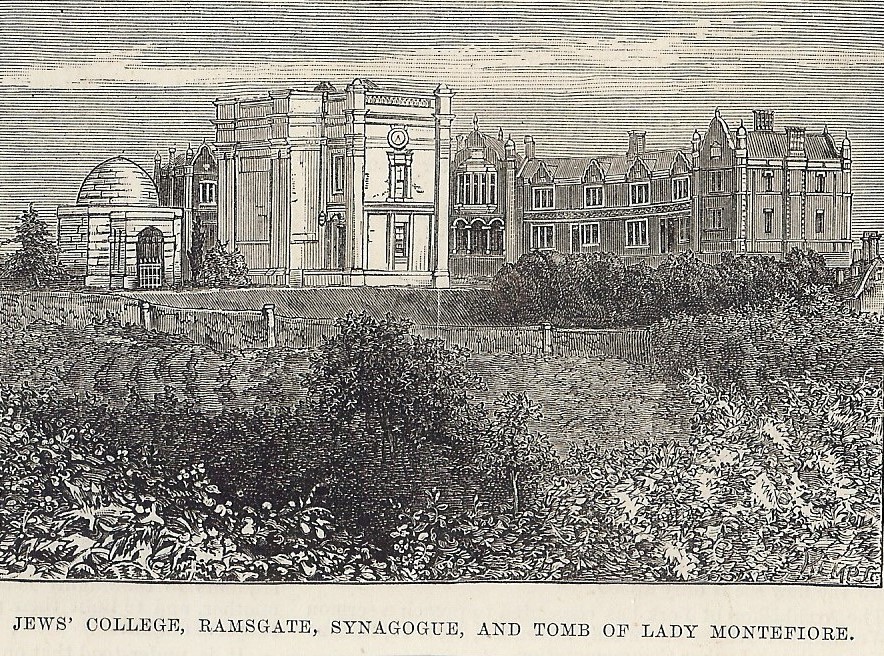

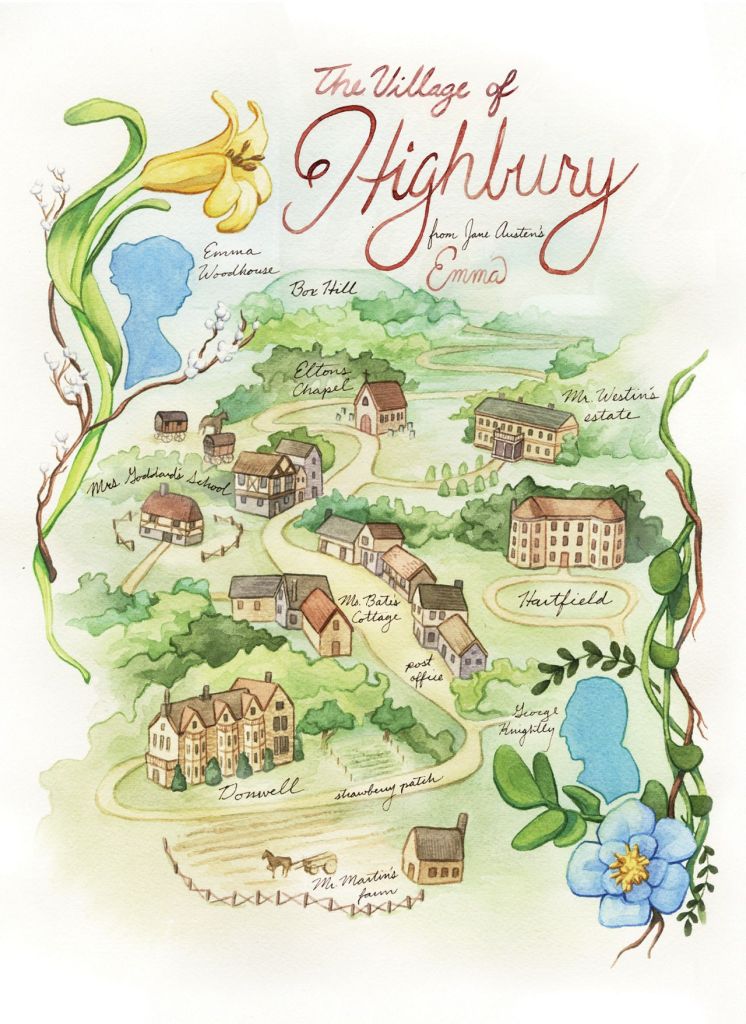

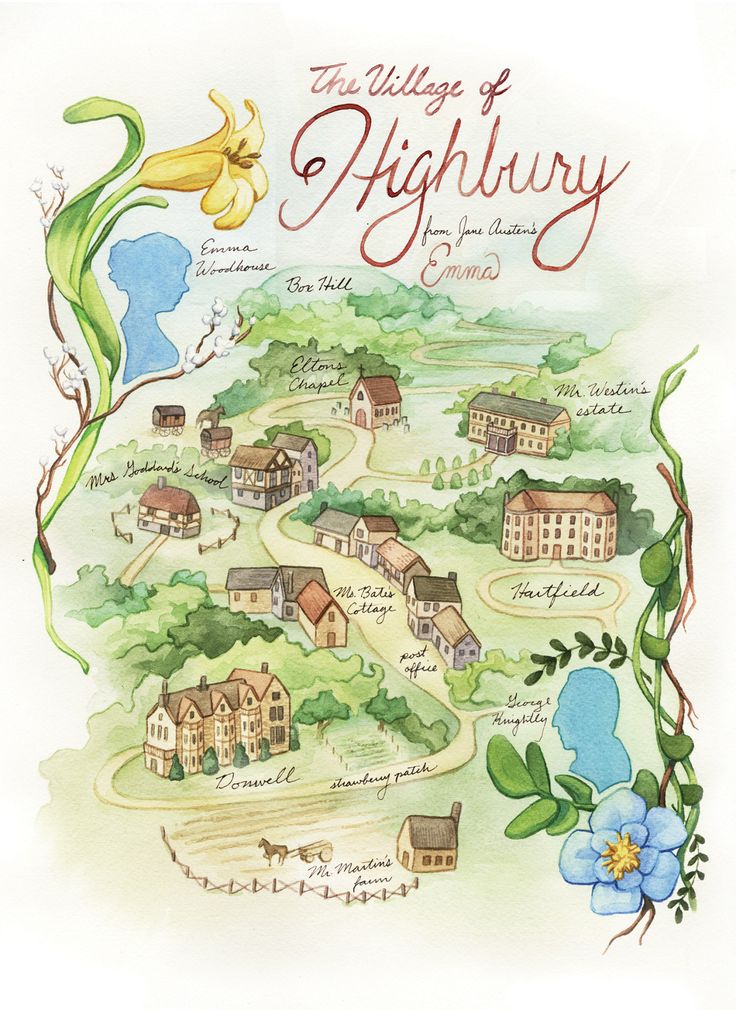

In my novels, these concepts are interwoven in Becoming Malka, Destiny by Design: Leah’s Journey, Celestial Persuasion, and most recently in The Jews of Donwell Abbey: An Emma Vagary. In keeping with Miss Austen’s playbook, my characters—Molly, Leah, Abigail and even Harriet Smith—all have a little trouble, but it is ultimately their faith and trust that helps achieve their Happily-Ever-After ending.

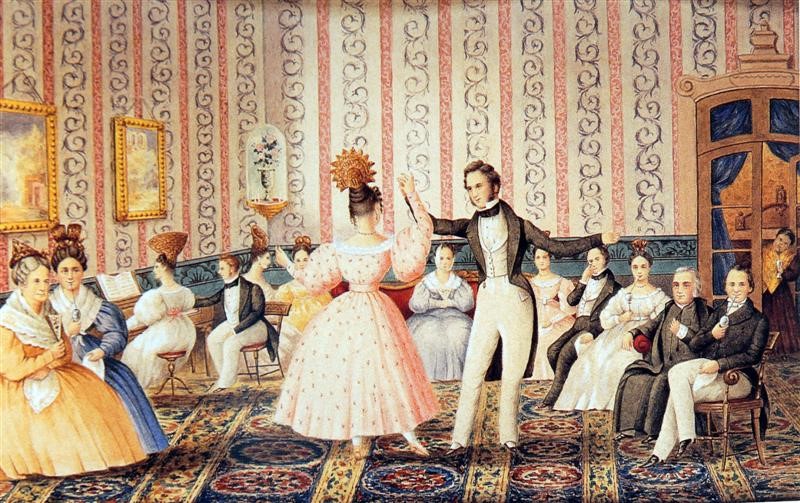

Of all my books, I think The Meyersons of Meryton highlights the Chanukah message best. In this story, due to a variety of unforeseen circumstances, Mrs. Meyerson—the rabbi’s wife—and Mrs. Bennet find themselves much in one another’s company. Miss Catherine Bennet (Kitty, as we know her) has endeared herself to the rebbetzin and her young daughter, Rachel. In a rather poignant moment, Kitty makes an emotive declaration and both Mrs. Meyerson and Mrs. Bennet are moved—most profoundly.

The passage below is a snippet of the final chapter, where Mr. and Mrs. Bennet have an interesting exchange.

An Excerpt from The Meyersons of Meryton…

When the happy couples at length were seen off and the last of the party had departed Longbourn, Mr. and Mrs. Bennet were found in the dining room quite alone, sharing the last bit of port between them.

“What shall we do now, Mrs. Bennet, with three daughters married?”

Surprised at being asked her opinion, Mrs. Bennet gave the question some thought before replying. “I suppose we have earned a respite, husband. Let us see what Life has in store for us.”

“No rest for the weary, my dear, for soon Mary will leave us and then Kitty. We shall have to make arrangements for the inevitable. Perhaps you shall live with one of the girls when I am gone and Mr. Collins inherits the place.”

“Mr. Bennet,” she giggled, “you should have more bitachon.”

“I beg your pardon?”

Perhaps it was the port, or perhaps it was pure exhaustion, but Mrs. Bennet found she had no scruple in sharing the entire tale of Chanukah with her most astonished husband. “Pray Mr. Bennet,” she finally concluded, “what was the true miracle of this holiday?”

“The logical answer,” he replied dryly, “would point to the miracle of such a small group of men overcoming a fierce and mighty army.”

“No, that is not it.” She giggled, as a hiccup escaped her lips.

“Well then,” he sighed, “the esoteric answer would point to the miracle of the oil lasting eight nights.”

“No, Mr. Bennet. Again, you are incorrect.”

“Pray tell me, wife, what then was the miracle, for I can see that you may burst with anticipation for the sharing of it!”

“The miracle, sir, was that they had bitachon. I do hope I am pronouncing correctly. At any rate, it means trust. They knew they only had one vial of sacred oil and had no means to create more. They lit the candle and left the rest up to the Almighty. And that is exactly what we should do in our current circumstance.”

“My dear, it is a lovely tale and I am certain that it has inspired many generations before us and will inspire many generations after we are long gone, but it does not change the fact that Mr. Collins is to inherit Longbourn…”

“Longbourn is entailed to Mr. Collins if we do not produce a son.”

“Yes, and well you know that we have produced five daughters, although you are as handsome as any of them, Mrs. Bennet. A stranger might believe I am the father of six!” he said with sincere admiration.

“You flatter me, Mr. Bennet. I certainly have had my share of beauty, but I wish to say…”

“You were but a child when we wed,” he waved her silent, “not much more than Lydia’s age, if I recall. But, my dear, that is neither here or there, for in all this time a son has not been produced and there’s nary a thing to do for it!”

“Mr. Bennet, there is something I have been meaning to tell you. That is, if you could spare a moment of your time—or does your library call you away?”

His wife’s anxious smile made him feel quite the blackguard. Had he not made a promise in Brighton? Did he not vow he would change his ways? Mr. Bennet decided it was high time he put the good rabbi’s advice into practice. Bowing low, he replied, “Madam, I am your humble servant.”

Happier words had never been spoken.

No matter which holiday you celebrate this December, whether the lights of your chanukkiah or the lights of your Christmas tree shine brightly against the dark, wintery nights, I hope your home and your hearts are blessed with peace.

With love,